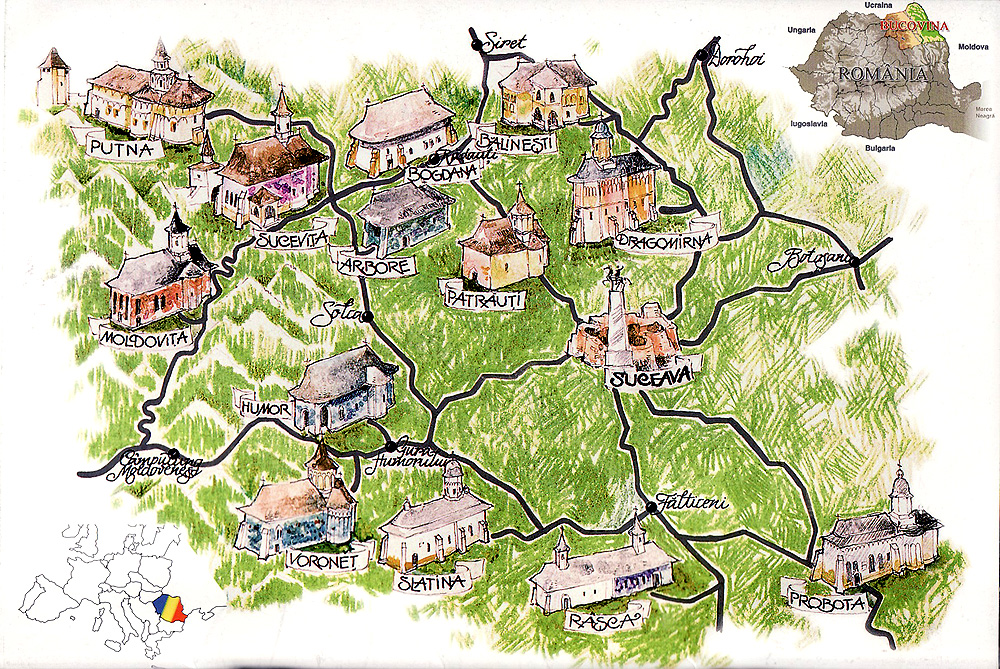

Bucovina monasteries

This is a story of storks, apocalypses, and level crossings. This is a story of stepping on cow shit, lapis lazuli, deafmute monks, and water wells in front of beautiful houses. However, this is above all a story where the concept of Time collapsed for me, where the passing of ages disappeared.

I will never remember it perfectly, anyway

Bucovina is a region between Romania and Ukraine and is part of the geographical region of Moldova.

I understand your concerns: do not be ashamed. Do not blush if you too, like me, cannot answer any of the following questions:

- What is the difference between Moldavia and Moldova?

- Is there a difference between Moldavia and Moldova?

- Isn’t Moldova a river?

- What language is spoken in Moldavia and Moldova?

- What about Bessarabia and Transnistria?

With pseudo-evangelical tones, I can tell you that life continues on without this kind of answers.

However.

However, geography is important, and history is even more vital.

Here is the Word, transferred to you directly from a valuable and reliable source:

https://www.eastbook.eu/en/2013/06/19/whats-in-a-name-moldovia-moldova-or-the-republic-of/

Mulţumesc

They say there are 2000 of them.

But it is not possible.

They say they are as beautiful as the Sistine Chapel and the Orvieto Cathedral.

Stop the nonsense.

They say so!

But Italy is the most beautiful country in the world.

Well… They say it’s worth it to travel to that part of Romania.

Oh well, it’s up to you!

In June 2019, I went to Bucovina to see its monasteries.

With the exception of Bogdana (built in the late 14th century), these UNESCO heritage sites were built between the 15th and 16th century by Stephan the Great and his (illegitimate!) son, Petru Rares, champions of the resistance of the Orthodox faith against Muslim and Catholic expansionism.

From Italy, I flew (via Bucharest) to Iași. From there, without a rental car, this trip would have been almost impossible due to the total lack of a public transport system outside the larger urban centres.

From Iași, the roads brought me up to the north: the landscape is as soft and welcoming as an old friend who knew of my arrival and who then prepared days of sunshine and languid air and horse-drawn carts dressed up like they were going to a party.

The roads towards Probota, my first destination, are filled with sheaves of wheat hanging on tall structures that allow to take out the humidity of the summer that has just begun, and with level crossings: you slow down near the train tracks, look to one side and then the other, and then you continue further. It is a wide flatland where breathing becomes easier, where there are no landfills or factories.

We stopped many times on the sides of the roads: we bought apricots and cherries, we got some water from country fountains and we reconciled ourselves with the movement of nature. In front of the fences, farmers are sitting on benches, resting, waiting for the sunset, talking about the same things as the day before, waiting for dinner.

From the countless light poles, thousands of storks look at us: they stand up there on their huge nests that offer shelter and rest to sparrows and swifts, and they take care of their young ones (which are gigantic). Faced with the simplicity of the animal world, I become a child again: I greet them, I talk to them, thinking stupidly that they can reciprocate and tell me what they see from their little houses.

A few kilometres from Probota, I stop to photograph them and end up in cow shit.

Yes, in cow shit.

I am wearing new sneakers. Pink and grey. I think they look splendid.

But now I am in deep shit up to my ankles.

Maria Teresa, my great travel companion and pilot in this itinerary, laughs and shakes her head. The blue gate of the house opens up. From the shadow of the pergola, a farmer approaches and begins to chat in Romanian. That theory of English as a global language fails so often around the world, and especially in this part of Europe.

That approaching movement, that offering of help without expecting anything in return: this is what travelling means to me. This movement makes the world a place for which it is always worthwhile to smile, to live, to trust.

What have you done, let me help you, I think he tells me as he opens the door to the well that completes his home? He laughs while he is slowly spilling water on to the stinky part, and then he points to the little storks. I think he tells me that there are three up there, but sometimes even more: storks’ nests are crowded places!

Where do you come from?

Italy, Turin.

Juventus.

No, Turin.

And we laugh as if it were the best conversation ever as if we had seen each other the night before in front of his house. I think that life is simple, after all.

Goodbye, and thanks.

Mulţumesc.

Probota and Râșca

From Iași to Probota, it takes about 2 hours by car. We park in a deserted parking lot, right in front of the monastery. There are a couple of gardeners who arrange the flower beds in bloom. There is a couple of pilgrims walking around this beautiful garden, and at the entrance, we are welcomed by a grim little nun who charges us for the entrance (5 lei per person) and the fee for taking photographs (10 lei per visit) inside this monastery, which was founded in 1530.

Crossing the threshold, my heart beats as fast as I were in love.

In front of me, there is an endless series of angels and saints dressed up like warriors, and up there in the middle of the central dome, there is the Christ Pantocrator who blesses the creation with the three fingers of his right hand. Daylight filters through this silent twilight. As happens in all the other monasteries, in Probota the founding family appears on one of the main walls: the father holds the representation of the church in his hand and hands it to the Madonna, and behind him there is his family, all wearing crowns, looking at us from distant ages.

Time and historical and political ages that separate me from the artists who painted these walls more than five hundred years ago evaporate: any kind of gap disappears, and we are together, close together, without tension. Only our steps resonate in this capsule of history.

After half an hour, we get to Râșca (founded in 1542). The green roof of the monastery towers up towards the grey sky in this hot and humid afternoon. At the entrance, there is only a cat with a lopsided eye that walks bored among the poppies: here nobody asks to pay anything. The monk who greets us is deaf-mute, but his smile tells more than a thousand chats. He beckons us to enter.

I do not know if it is because in Râșca we really have not met anyone and therefore the experience has been more intimate, or because in some strange, inexplicable way, it is possible for some places to retain the memory of past events. I only know that Râșca (with Arbore, of which I will speak later), with his frescoes blackened by centuries, with his immense candelabrum, with his monsters – wolves of the Apocalypse that nibble the souls of the damned, with his continuous chiaroscuro, for me it was the most ephemeral monastery, the most spiritual and ethereal, and therefore the most unforgettable of the whole journey.

Stop it immediately

Every single guide and website will tell you that Voroneṭ is the most beautiful and the most important of the Bucovina monasteries. They will tell you that it is the Sistine Chapel of the East, that the Last Judgment covering its outer walls with angels and demons at the end of days is unique in the world.

That that blue there, made of lapis lazuli, is very rare and has even become a colour of its own, like the red of Titian and the green of Veronese. They will tell you all these things rightly, of course, because this monastery is incredible with its frescoes that tell not only the end of the world, but also other biblical parts like the Genesis, the sacred hymns, and the Tree of Jesse, and then they also depict Plato and Aristotle.

But.

Obviously, there is a but.

Getting to Voroneṭ, an hour or so from Râșca, was an alienating experience to me: the two buses overflowing with German tourists screaming and taking pictures as if the lapis lazuli were about to evaporate, the sound of their chatter and the explanations of their guide barked inside a megaphone, the warnings of the religious personnel against these “athletes of the selfies” who did not understand why they could not use the flash inside the monastery did not make me appreciate this place as I probably should have.

Faced with such demonstrations of socio-cultural illiteracy, I cannot help wondering why people decide to travel to places like these: what do you come to do in Bucovina if when you arrive in this spiritual region you don’t even have the decency to lower your voice? What are you hoping to find here? What do you want to prove to the rest of the world? That you travel to alternative places and hence you are special? I ask these screamers: do you really know what you are looking at?

From Humor to Bardonecchia

With the last monastery of the day, it went better. Less than 15 minutes by car from Voroneṭ, we arrived at Humor (founded in 1530). In the distance, a storm was getting ready to cool the air at least for the night.

Humor is the first of the Bucovina monasteries to have been frescoed: its paintings, characterised by a red ochre shade, speak of the Last Supper, but above all, they tell of the siege of Constantinople in 626 by the Persians. However, the Persians on the walls do not look Persian at all: they wear turbans that makes them look very Turkish. By distorting history, in all the hermitages of this part of Romania, the frescoes were used for political propaganda in addition to the spiritual one. On these centuries-old walls, the Persians became Turks to remind the peasant communities the real enemy that Stephen the Great and Petru Rares had boldly defeated.

Of Humor, there is another element that stuck in my head: the myriad of signatures of those who arrived here in the past centuries and engraved their name under the effigy of this saint or of the Madonna. Some have been scratched in Latin italics, others in Cyrillic, they come from far away geographically and historically. They say I was here, it was 1889 or 1724, I was called Joseph Kadar or Medresh or Alexandr. I am no longer alive, but I remain eternal in this wound, near these blessed, near the trumpets of the Apocalypse.

Probably what I am about to say is nonsense, but these scribbles and scars could help to retrace History. They could tell us about the movements of peoples. What did those who came to Humor in the 1700s look for? And above all: can you imagine what they must have seen, back then? What Humor must have been like and the Carpathians and all the monasteries in Bucovina in the 1700s!

At the end of the first day of the journey in Bucovina, Maria Teresa and I slept in Bardonecchia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bardonecchia). What the fuck is she talking about, you’ll think. Bardonecchia is not in Romania. Bardonecchia is in the Upper Val Susa, in Italy. But yet. Yet, Gura Humorului reminded us of the Piedmontese municipality which is famous for winter sports: it was the sparkling mountain breeze, the fir forests that kept us company while we were approaching the town, the delicate houses, the small bridges in the centre, the roundabouts adorned with flower pots! Sometimes, Bardonecchia happens just when you least expect it!

From Moldovița to Putna, and a border that cannot be found

On the second day of our journey, we visited the monastery of Moldovița (built in 1532) and from there we continued up to the Pasul Ciumarna pass: it can be reached by following the DN17A, a paved road in the middle of the Carpathian fir forests.

Unlike the indications found on some travel sites, the road is everything but dangerous: your eyes will rest while driving along these 15 kilometres of bends and twists. We stopped for coffee at the Monumentul Drumarilor, a 7-metre-high hand built here around the end of the Sixties as a symbol of work, but also of strength – pointing towards the heights of the air at about 1000 metres above sea level.

The next stop was the Sucevița monastery (built in 1585) and from there again to Marginea, a small town which is famous for its black pottery. According to historians, the beginning of production of this special type of ceramics dates back to the 16th century, but ceramics have played an important role in the development of even more primitive societies as it has made it possible to preserve food.

Before the Communist regime, there were at least 60 families of ceramists in Marginea. We see only a couple of them at work: the movement of the hands of the artisans who smooth and shape the clay on tiny lathes is hypnotic, and makes me feel a bit inadequate because I realise that I can’t make anything with my hands. I am totally incapable of creating something material: perhaps this is the curse of generations like mine, where everything is virtual or intellectual, or at least intangible.

30 kilometres further from Marginea lies Putna, one of the first monasteries built by Stephen the Great, whose construction began in 1466. There are many students in its garden when we arrive there: while I am looking at them in their uniforms and their traditional costumes, I realise that all schools are similar in the world: some students chat among themselves, some talk with the teachers, some wander a bit isolated from the rest of the companions.

In this case, however, some step on a small stage built in front of the statue of the Romanian romantic poet Mihai Eminescu: I don’t understand anything of what is being said, but I think they are declaiming famous poems or singing popular folk songs. Maria Teresa and I stand there still and silent in the almost unbearable June heat: we look a little like two statues of salt, because we observe them without any reaction to their performances.

You know, I think the border with Ukraine is not too far away, I tell my friend. Didn’t we see the sign to the border earlier on? And like that, we are back to the car and we want to go and see the border with Ukraine because according to the navigator it is there less than half an hour. We wouldn’t have crossed the border, because it’s often not possible to do it by rental cars. However, we want to see a limit, that stupid convention that you can’t see from space but that often holds so much importance here on Earth!

We drive back and forth, here and there, and that sign that we both saw before disappears, we can’t find it again, and we stop – exhausted – in the middle of a village that in reality is only a couple of houses. We ask two peasants on their bicycles how to get to Ukraine, and they tell us in Spanish that customs no longer exist there. And how did it disappear? I don’t know, it’s gone. You have to go far, more than an hour and a half from here. So, goodbye Ukraine, maybe I’ll see you next time.

Bogdana, but above all Arbore

Our expectations on Bogdana are very high and therefore the disappointment becomes despair when we get there: the oldest monastery in the country, founded in 1360, has been closed for a couple of years for restoration works. The nun who greets us at the entrance of the site is sorry, but she suggests that we briefly visit the new monastery a few steps away.

And there, something a bit absurd happens: it’s one of those paradoxical and incomprehensible situations that – I think – can only take place when you travel. On the floor, on the carpet in front of the iconostasis, there is a woman dressed like a circus trapeze artist and a go-go dancer: glittering sequins, wedge heels and a huge wig. Two family members (or friends, who knows) keep her on the ground and are pushing the Bible (or some other kind of holy book) down onto her head.

She doesn’t move, she lies there as if she were dreaming as if it were the most normal thing in the world. No one seems to mind, except for Teresa and me. Instead of enjoying the architectural beauty of the monastery, we sit and look at her – we actually stare at her! No one pays any attention to us either. After 20 minutes of total stillness, we get up and leave laughing.

Maybe it was an exorcism. Maybe they were drunk. Maybe. Maybe. Maybe.

And then, Arbore, magical and ethereal as Râșca. We arrived at the monastery at the end of the second day: the afternoon air is so hot that it seems palpable, but once we pass the small gate, the shadow of the trees caresses our hearts. A very light wind rises and moves the grass around the two or three tombs that are in front of the monastery. We sit down there on a bench that is a little crooked, in silence, watching the frescoes: they are starting to fade, and Time is melting again.

Inside, then, in the chiaroscuro of the monastery walls, we look at the Decapitation of St. John the Baptist, and we chatted (in what language, then?) with the nun of the monastery. Where do you come from? The most beautiful question. Come inside, you are welcome here. The most loving sentence.