Craiova: a few considerations about Europe

It is dark from above in this part of Romania. Like a dreamless, peaceful sleep. Sitting up here, at the back of the plane, I begin this little journey towards an unusual destination in this beautiful Europe where I have the shameless fortune to have been born and raised. Many flights from Turin to Romania leave late in the evening, so I land in Craiova after midnight. I call an Uber (an Uber! Unthinkable in Italy!) which shows up without any problems after about 7 minutes and takes me smoothly to the hotel where I will sleep for the next 3 days. The entrance is through codes which were emailed to me a few hours before by the owners. I will never meet them, but they will wait up for me to make sure I get to my room without any problems. We communicate in near-perfect English during my stay. I have the feeling – not at all fictional, believe me – that they have thought of this hotel as a cosy home, rather than a place to pass through. On the bedside table, new, I find an essence diffuser, new. The bed, new, has a duvet and quality sheets, also new. Good night Craiova.

Calling March

These days, many European nations celebrate the arrival of March. In the village where I grew up until my university years, we ‘call March’ and every so often this coincides with heavy snowfall. In Romania, Albania, Bulgaria, Moldova, Macedonia, and Greece, the beginning of spring is celebrated with a holiday identified by different names depending on the country. In Romania, this festivity is Mărțișor: it is a festival with very ancient origins, as always complex or almost impossible to trace, but here in Romania it certainly predates the Romanisation of the nation when the Dacian civilisation honoured the rebirth of nature. In the morning, when I leave my house hotel, I immediately realise the special occasion: the pedestrian centre is full of stalls where one can buy small amulets, usually for girlfriends, wives, sisters, and children. These small objects, images of love and good luck, always have two colours: red, representing spring just around the corner, and white, symbolising the winter that has just ended.

I leave Mihai Viteazul Square behind and walk for about a couple of kilometres along Calea Unirii, a street full of doctors’ offices, hospitals, a Fresenius dialysis centre, and many Brancovenesti-style houses, arriving at Nicolae Romanescu Park, where spring is truly in the air. The neat and tidy park is a true historical document: in 1898, after Romanescu was elected mayor of the city, a project for the modernisation of the city was voted in. One of the objectives of the programme was to create parks and gardens. The winner of the competition was the French architect Edouard Redont, who took his plans to the Paris Expo in 1900 and won the Gold Medal. Redont was a tough guy: for the Craiova park, he decided to introduce hundreds of plants that don’t normally grow in Romania; he designed a medieval castle; he built a Suspension Bridge that connects two mounds and mistakenly reminds me of the one in Brooklyn. He added hills and valleys, roads, and paths for a total of about 35 kilometres. I walk for a few hours in this green lung of the city, a perfect synthesis between a painting and landscape architecture. I stop for lunch at one of the jetties overlooking one of the park’s artificial lakes: a salad accompanies thin, delicately flavoured carnations and a coffee. There are no travellers on this early February afternoon. I stand there, watching families and groups of friends come and go, sharing a dish or a lemonade, and as often happens I don’t seem to have another life elsewhere.

In the afternoon I go to the Alexandru Buia Botanical Gardens. Most of the plants here, as at Romanescu Park, are still dozing, while some daffodils are stretching shy but determinedly out of the ground. I wonder how beautiful all this will be in April, and May when nature will be in full bloom. In the 1950s, it was Buia, a professor of botany and agronomy at the University of Craiova, who wanted this green area to be created. 13 hectares, 3 artificial lakes, the Botanical Gardens are also full of statues and artistic installations, but for me, one of the most beautiful parts is the Lovers’ Bridge: here two rows of ornamental potted flowers glide towards the small pond that surrounds the area. On the Bridge of Lovers, however, there are not two lovers as I pass by, but two friends a little bit older, one of them clearly deaf because he talks very loudly. They seem to comment on the geese and swans frolicking in the water at their feet. No matter where they are in the world, images like these, of friends laughing at nonsense, joking about who’s telling the tallest tale, are ultimately the ones that stay the longest in my memory.

What defines a Journey and a Traveller?

In Craiova, I don’t meet any other international travellers: this situation, besides being highly pleasing to me, also leads me to think about how one can or should precisely define a Journey. Does Travel mean visiting the very same destinations? And then the same ones for whom? Or is it better never to lose curiosity and to continue to seek out even destinations that are often considered secondary, a little mistreated, because perhaps it is precisely those that have still retained a minimum of authenticity, that offer a glimmer of everyday life not yet totally watered down by the globalisation of which we are products? Obviously, I do not have an answer to all these doubts. I don’t have many answers in general in life.

On my way out of my hotel this Monday morning, I meet many students, both university students and younger ones. Children are the same everywhere, here in Oltenia as well as in Sydney: they hold hands in pairs as they cross the street following the teacher, chatting, laughing, and goofing around.

The first Orthodox church I visit is the Church of the Holy Apostles, one of the oldest religious structures in Craiova (originally built in the 15th century). The pope and one of his aides must not be very used to travellers, because as soon as they see me, they invite me in. Romanian and Italian are not the same language, but I understand that they are asking where I am from. I know where I live, but not where I come from: once in my life I would like to answer like this to see the reaction of my interlocutors. Just like that, just to create a bit of a mess. Because it is the truth: after all, what defines the origin of a human being? Their passport? Their birth family? The culture or nation one is born into? Or what one acquires through different channels? Because I would really like it if it were possible to say: ‘I am European’, I am the daughter of this continuous mixing of languages, of nations that you know where they begin but not where they end, I am the daughter of peace and of a thousand wars, I am the daughter of Italy, but also of Ireland and Greece, I am a product of the thousand winds that have shaped the Carpathians, the Caucasus, the Alps and the Balkans, I am a product of the Danube, the Po, the Vistula, the Shannon. But to the clergyman who invites me inside the church, I answer that I am from Turin.

In the Metropolitan Cathedral of Craiova, no one asks me anything. The temperature inside offers shelter to an endless line of old ladies so stereotypical with their headscarves on that they look fake. There are also two homeless people, the only ones I meet several times in the centre of Craiova during this short stay. Churches are not only crowded but also on the move in this part of Europe: the faithful come and go from one icon to another. These movements always amaze me, because, in temples of other Christian faiths, I have often felt obliged to be stationary so as not to disturb the deities. Another thing I notice in this church with its gold-coloured walls is that several clergies officiate at the service: they stand to the right of the ever-present iconostasis, taking turns reading and chanting a couple of holy books resting on a lectern that rotates. That is why the lectern has to rotate. I have visited dozens of other Orthodox churches in my life, but for the first time, I notice this: travel gives us new eyes, and makes us more aware and more present.

As I leave the cathedral, I find only one thing strange: there is no parking for the faithful. I try to talk about it with some people I meet on the benches – new ones – surrounding the church. This time, too, the proximity of Romanian and Italian helps me: I understand (perhaps) that parking spaces are there, but (perhaps) they are metered and therefore few can afford them. That the diocese (perhaps) receives a portion of these fees. I don’t know what I can use such detail for in the future, except to argue once again that churches are all big money-eating machines, no matter what orientation they are. Perhaps.

The next stop, very close by, is the Church of Our Lady Dudu. I sit on the floor because in Orthodox churches there are almost never chairs and I witness a fairly long series of confessions amidst the usual coming and going of the faithful from one sacred image to another. They are all women, of all ages, who approach the pope with sins that, at least judging by their appearance, cannot be mortal: what kind of unforgivable mistakes could these women have made? They all seem like good people, and I wonder what eats at them inside, I wonder what corruption and anguish can gnaw at their souls. The confession happens in a very physical way, here: the believer is blessed by the cleric, she kneels at his feet, and he covers her head, the nape of her neck, with the scarf symbolic of her spiritual role, decorated in silver on a black background. Is it a symbol? Does God protect you, or will you let me protect you from the wrath of God? Another idea springs to mind: the further east one goes, the more physical faith seems to me to become, and the more contact there is. Just think of the kisses that Orthodox believers give to icons. I don’t know if this behaviour bothers or annoys me: touching has become taboo, and it has become something complex and compromised in the pandemic years. Who knows what pain Covid has brought here with bodily distance from the faith?

The Church of St Nicholas is closed to the public when I arrive there in the early afternoon: I am informed by a girl as soon as I enter the courtyard. I then notice that the young woman’s left eye is harnessed in a huge pair of false eyelashes, while the right is without make-up. She speaks little English, but tells me I can have a look at the frescoes decorating the church entrance: those on the right wall are a representation of the Trumpets of the Apocalypse, along which blue devils do unspeakable things to kings, queens, wolverines, and sinners in general. Christians are always so merry. .

The last spiritual stop is at the Church of St. Iliei: the pope stands welcoming the faithful who come and go and holds a candle so big it looks absurd. To his right, there is a small table on which a woman is ironing. Yes, she is ironing. And she talks on her mobile phone and occasionally greets those who come in and out. Perhaps this is what I like most about Orthodox churches: they are lived, because life is also, alas, ironing clothes.

No one can stop me

In Craiova, I spend the vast majority of my time alone, without anyone stopping me or asking me anything. This is also the case at the University, where I enter and visit a couple of completely deserted and surgically clean lecture halls and halls, and also at the Marin Sorescu Theatre: located in William Shakespeare Square and built according to the dictates of Brutalism, it was founded only 165 years ago and since 1989, a pivotal year in European history, it has participated in several international festivals. Since 1994, it has also organised a very important festival dedicated to the Bard. I cannot help but wonder at this point what they might have staged during the years of the communist regime: an almost endless series of plays steeped in the empty rhetoric typical of all dictatorships in the world.

I am also alone when I arrive at Cofetăria Minerva. Surreal is the only adjective I think I can come up with once I sit down for coffee and cake. It resembles a ballroom, with marble tables, chairs, sofas, and walls in shades of red and green damask. Rich ceilings, almost too much. The lady behind the balcony listens to a radio that plays only and exclusively Italian songs: some artists from the recent Sanremo Festival are followed by others that are not really famous outside Italy.

Monsters

On the morning of my last day in Craiova I go to the Oltenia Museum – closed on Mondays – which is in a spectacular building opposite the Church of the Madonna Dudu. There are a few classes of middle school kids visiting the building with me, and I think it could really be an exceptional cultural centre if only some of the explanations – presented on huge, detailed panels – were in English. I try to do the online translation of the first few rooms, but I tire easily because it is quite an absurd mechanism.

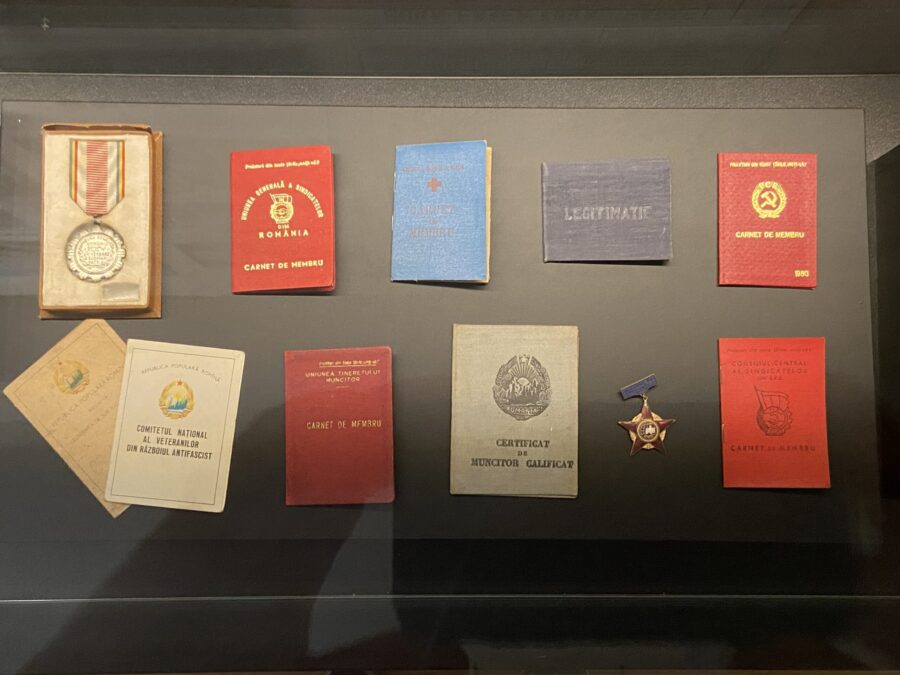

However, I decide to commit myself at least to those dedicated to History closest to me, that is, from World War II onwards. In one of these rooms, we talk about the ruthless repression that the communist government imposes against those citizens who are obviously, once again in history, considered enemies of the system. Internment camps are created in line with those of the Soviet prison system: prisoners’ rights are inhumanely restricted, food was reduced, and punishments become harsher and harsher, until the Piteşti Experiment.

What happened in this prison a few hours from Craiova, between December 1949 and December 1951, represents one of the most obscene mass re-education experiments ever: in addition to an absurd series of psychological punishments, the internees – most of whom were students – were subjected to physical torture by other internees. Let me explain: in this article published in 2019, it is recounted how the prisoners had to go through 4 stages of re-education or unmasking. In the first, referred to as external unmasking, prisoners had to prove their loyalty to the Party by revealing their various links to ‘enemies’, links they had concealed during Securitate investigations before being sentenced to prison. In the next phase or internal unmasking, the prisoners had to reveal the names of their ‘enemies’, i.e. those who were less brutal towards them inside the prison. The more fictitious the enemies, the greater the prisoners’ chance of moving on to the next phase, called ‘public moral unmasking’. During this third phase, victims had to disown their family or close friends and their religious beliefs. Finally, in the fourth phase, prisoners were forced to re-educate their best friends, thus losing their status as victims. Obviously, a failure at any subsequent stage sent the inmates back to square one. In this obscene system, moreover, death was not an option: many students did not attempt extreme beatings, but longed for them out of desperation. It was the only option to give death a chance. Unfortunately, those who did the experiments knew this very well: the torturers in the cells knew it too, because many of them had wished for the same when they were in the same situation. The command was categorical at Piteşti. Blows to the temples, directly to the heart, the back of the head or any other part of the body that could lead to death were not allowed. The physical death of the students was not necessary.

The explanations in the halls continue with descriptions of what happened later in the 1980s: the second oil crisis (1979), Romania’s economic deficit, the long period of austerity imposed by Nicolae Ceaușescu (I wrote about it here) resulting in a halt to the use of natural gas for domestic heating in 1982, and a ‘food security’ programme to regulate the amount of food consumed by the Romanian population.

I’ll state the obvious, I’m sure, but we are monsters and indeed History runs in circles.

[If you are interested in the other articles I wrote about Romania, please visit here]

Loved this. Thank you

Glad to hear it, friend 😉