Florence: the beginning of the cure

And yet

It is practically impossible to talk about Florence without sounding predictable, without mentioning Brunelleschi’s Chapel, Giotto’s Bell Tower, the Uffizi and the Arno River. It is difficult not to say things that have already been said by so many before us, by millions of tourists and travellers who have come here, throughout the centuries, without listing obvious places.

And yet.

And yet, for me, the days in Florence were unique, unrepeatable perhaps, because from February 2020 to June 2021, Dante’s city was the farthest destination I had ever come.

It sounds absurd: I was used to crossing immense distances. You’d get on a plane and bam, you were in Sydney, New York, La Paz. You’d wake up half dead after your flight and there, tens of kilometres below your feet, the world had turned upside down, moved and you with the earth had crossed continents and countries and borders and skies without doing anything.

And yet.

And yet, the evening I arrived in Florence, in Piazza del Duomo, I had the feeling of seeing everything for the first time. I had already seen those coloured marbles over and over again in my pre-pandemic life, but in those last hours of the day, immersed in the typical June heat, I felt lost at first, as if I had never gone anywhere before. I stood there for an hour like an idiot. In hindsight, I realised that I wasn’t lost. I realised that I had found myself in Florence because it was there that I had somehow returned to live.

Yes, I understand: there are some travellers who are spasmodically trying to get to the end of the world, because travelling in Italy is a given for those who, like me, live here. Because they collect destinations on Instagram. Because nothing is ever enough. Don’t get me wrong, readers, I miss intercontinental travel too, I miss Asia and I wait for the US and South America as you wait for Christmas.

And I know that the day I get back on a plane will bring a joy that words cannot describe because it is as deep as a cave and as bright as a lighthouse.

But in my own small way, I think it is not sustainable to be so greedy – now – after what humanity has experienced. I think it is necessary to be grateful for the steps that – now – we are allowed to take. The rest of the world, although fragile and in constant flux, is waiting for us and will welcome us when everything is healthy. We must heal first.

The dozens of kilometres I covered in four days in Florence were the beginning of my cure.

San Frediano

A feeling of intimacy: this is how I would describe San Frediano, without thinking too much about it, without being an intellectual looking for precise and extreme words. A feeling of real life in a city that often gives you the idea of being a museum, an enormous marvellous display case.

No one pretending to be something they are not: at the bar, at the trattoria “‘l Brindellone” a stone’s throw from Piazza del Carmine, at the fruit market in a square whose name I absolutely didn’t note down, in front of “Paralume” (Borgo San Frediano 79) which produces lamps that seem to come out of a Wes Anderson film, inside the Cappella Brancacci (where you can see the first real Scream in the history of art painted by Masaccio) there are no tourists, just a lady cleaning the church floor and arranging the flowers on the altar. “It’s nice in here,” she says. I don’t know if she’s talking to me or to God.

No one pretending to be something they are not: at the bar, at the trattoria “‘l Brindellone” a stone’s throw from Piazza del Carmine, at the fruit market in a square whose name I absolutely didn’t note down, in front of “Paralume” (Borgo San Frediano 79) which produces lamps that seem to come out of a Wes Anderson film, inside the Cappella Brancacci (where you can see the first real Scream in the history of art painted by Masaccio) there are no tourists, just a lady cleaning the church floor and arranging the flowers on the altar. “It’s nice in here,” she says. I don’t know if she’s talking to me or to God.

And then there’s the Rondinella club, close to the historic Torrino di Santa Rosa. You pay 2 euros to join and become a member and then you can stay there as long as you want. I have a coffee at the bar while two bartenders swap afternoon shifts, and then lie down on one of the many orange deckchairs: next to me are two workers, wearing safety shoes, blue trousers with reflective bands, both asleep and one snoring. A guy next to me is reading a book and it’s obvious he doesn’t like it because he picks it up and drops it every two minutes. An elderly couple is sharing stories about their garden. A clatter of plates and forks, small tables but full of families and friends.

I’m standing there under a tree whose name I obviously don’t remember because I don’t understand anything about plants, but the scent that the wind moves through its branches is wonderful and I, like the two workers next to me, take a nap.

Museum of San Marco

A sea of children comes out of a small primary school, a few metres from the entrance to the museum: they chase each other and laugh freely, I wonder how they can move so much in the heat of the afternoon. I am greeted by Fra Angelico and then enter Savonarola‘s austere headquarters: tiny rooms that exude penitence and tell of punishments, cilices, heresies, and stories of the bonfires of vanities. In some corridors, you can see a few chairs which are named after the most famous tenant of this structure.

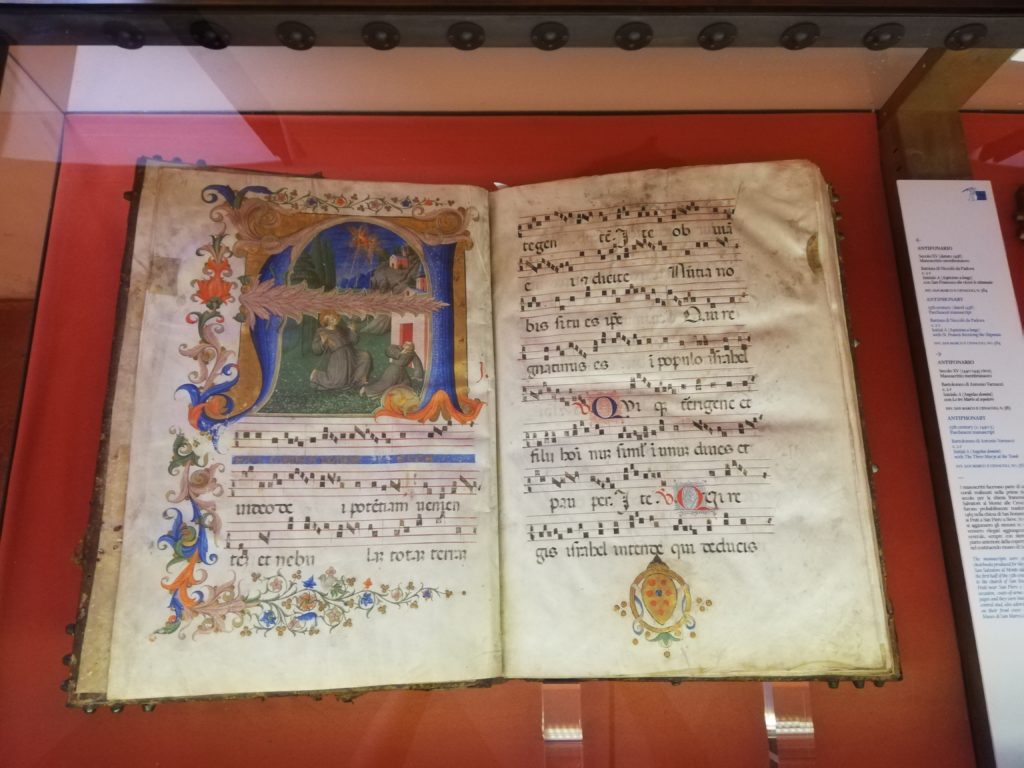

But above all the Illuminations: the Museo di San Marco includes a library established around 1430, housing manuscripts belonging to the Medici and to Pico Della Mirandola and Agnolo Poliziano. In front of the illuminated volumes, the centuries run through my head.

At the end of the room, two other display cases protect a series of colours used in the ‘Illuminations’, white lead, lapis lazuli blue, yellow ochre, vine black and gold. There are examples of the ‘styles’ with which the monks engraved the lines, of strong and flexible quills used in the transcription of the text, of scrapers to erase errors.

My memory, as I walk alone in this long room, takes me far away: it takes me in front of the Book of Kells, to its most famous page (Chi Ro) and a phrase echoes in my head: “Turning Darkness into Light”.

The wine holes

During my days in Florence, I walked a lot, really a lot. The city streets are almost empty: a few words in American and Nordic European languages can be heard now and then, but you don’t get drowned in the flow of tourists that you can usually meet on these streets.

One part of me – the more selfish one – is happy: I can stop as long as I want wherever I want. The other part, however, understands the problems that all this silence can bring to those who work in culture. In the darkest months of the pandemic, we often talked about restaurateurs: don’t get me wrong, they too have suffered. But it seems to me that the art world was another of those sectors that suffered from the absence of noise and revenue.

One part of me – the more selfish one – is happy: I can stop as long as I want wherever I want. The other part, however, understands the problems that all this silence can bring to those who work in culture. In the darkest months of the pandemic, we often talked about restaurateurs: don’t get me wrong, they too have suffered. But it seems to me that the art world was another of those sectors that suffered from the absence of noise and revenue.

This calm allows me to go and look for the buchette del vino: today there are more than 150 of them, and they were created in 1634, during the plague described by Manzoni. They were the sales points outside the palaces of the aristocracy who had wine estates and vineyards. They were used to retail wine along the streets of the centre of Florence. There were also those who, like Francesco Rondinelli, described their effectiveness in preventing contagion back then. The customer would knock on the door, the servants would take the money, disinfect the flask with vinegar and then put it back in the little hole full.

The same practice came back into vogue during the health emergency brought on by Covid: for example, the Osteria delle Brache in Piazza Peruzzi started using the anti-contagious door again. History does not repeat itself, but it does come back in rhyme.

The Zeffirelli Foundation

The Foundation is located in Piazza San Firenze, a few steps from Palazzo Vecchio and Piazza della Signoria. Entering this museum, dedicated to Franco Zeffirelli‘s creative craftsmanship, is simply entering Great Beauty: inside, in fact, there are several hundred works including stage sketches, drawings and costume designs, created during his long and truly multi-faceted career in prose theatre, opera and cinema.

I am the first (and perhaps only) visitor of the morning, but I don’t feel alone: there are many photographs of almost mythical personalities who have worked with Zeffirelli in cultural venues around the world, from Graham Faulkner to Laurence Olivier to Anthony Quinn, from Maria Callas to Anna Magnani, from Luchino Visconti to Pirandello, from Richard Burton to Elizabeth Taylor, from Placido Domingo to Pavarotti.

The most fascinating part for me, however, is Room 14, the Sala Inferno dedicated to the project on Dante’s Inferno that Zeffirelli never realised. Fifty-one sketches are on display here and projected scenographically on the ceiling and walls. I can’t tell you why, but I stay in this room longer than in the others. Looking at the sketches on the walls, I remember, as if in a game of mirrors, a high school teacher who had explained to us that in Inferno not only does everything follow a very precise pattern (punishment, demonic figures, the damned on duty who give voice to their punishment), but that from one circle to the next everything becomes crueller and crueller: the monsters and devils become increasingly evil and the punishments increasingly complex and evil. Perhaps it is the fascination with evil, the Darth Vader attraction.

Or maybe it’s another thought that keeps me sitting there for quite some time, as the illustrations of the damned keep on appearing on the screen. It is a thought that takes me back to Dante, to his world in which – to put it trivially – most people (except Dante himself!) knew where they would live and what they would do as a living. The world I find myself living in, on the other hand, has none of these huge certainties. For better, and for worse.