India: so much more than Bollywood pt.1

We’re still stuck at home. I’ll spare you the details of how I’m feeling while not being allowed to travel. You can imagine it for yourself, even if you don’t know me very well or you happen to be reading these lines on the other side of the world. Cinema has given and still gives me some comfort in this suspended time: I believe that Art saves, Art nourishes.

So, I thought I would write two articles on the Indian films I have watched in these 12 months of stalemate and make them available on this blog because maybe you too miss India. Or no, you don’t miss it at all, but you need a diversion.

Rest assured, I am not going to tell you about Bollywood. I’m going to suggest films that are more accessible for Western audiences, both from a visual and content point of view. Films that tell you about an India that – perhaps – you would not expect.

Let’s start.

1983 – Heat and Dust

I like to start this list with a story about women. Anna is a BBC journalist who returns to India to investigate the story of her adoptive grandmother, Olivia. Olivia, in the 1920s, is in India in an unnamed town following her husband and has an affair with the local Nawab. “Heat and Dust”, apart from being a story of faltering customs and social restrictions, tells you about the attraction and repulsion between two immense cultures (the Indian, and the British). If you liked David Lean’s “Passage to India”, “Heat and Dust” is also for you.

Ps. The film is based on the book of the same title by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. Ask your local bookseller.

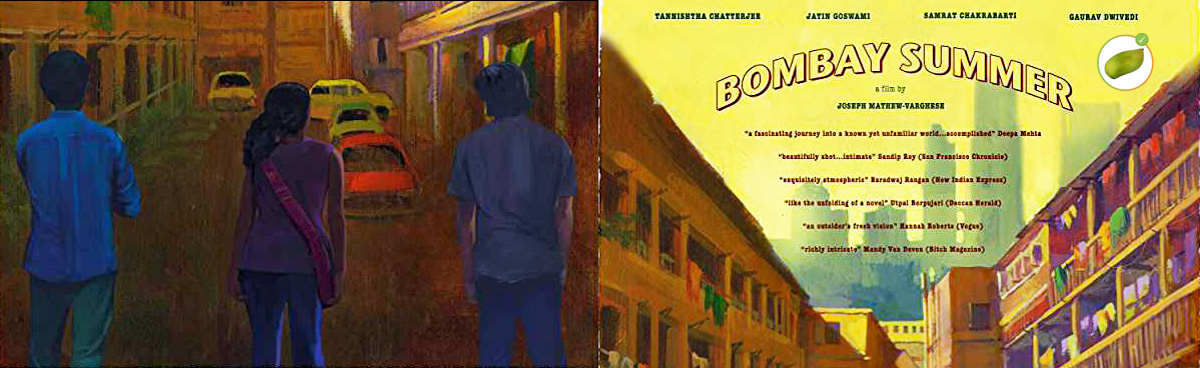

Bombay Summer (2009)

“Bombay Summer” looks like a Bollywood movie, but the only singing or dancing takes place on old records and in a cocaine-infested nightclub. What’s more, it tells of a love triangle between Jaidev (Samrat Chakrabarti), an aspiring writer from a wealthy family; his girlfriend, Geeta (Tannishtha Chatterjee), a design director working in a modern office which will remind you of those in London; and Madan (Jatin Goswami), a struggling artist who supplements his income by delivering drugs. It is the latter who seduces his new friends largely by giving them access to an older, poorer (and therefore truer) India – through the vintage records he collects, the Hindi movie posters he copies, the old chawl (apartment block) where he lives and the seaside village where he grew up.

A Death in the Gunj (2016)

A Death in the Gunj (2016)

For this film, I am biased. I am biased because it stars one of my favourite Indian actors, Vikrant Massey. Many describe “A Death in the Gunj” as a horror movie. And indeed, the story opens with a dead body being placed in the boot of a blue Ambassador. The setting is McCluskieganj, a town in north-east India in the 1970s, an area haunted by the spectre of the British colonial empire. Shutu (our Vikrant Massey) is a troubled university student whose father has just died and is visiting his aunt’s house. Here a twisted family dynamic slowly begins to develop around him: Shutu’s cousins and their friends find increasingly cruel ways to torture him; they start with a prank involving a séance and eventually leave him in a wolf-infested forest. But beneath these ‘gender games’, there is a masterful depiction of how the deeply rooted patriarchy in a nation like India can rot a family tree. Shutu, in fact, is tormented for his crimes against masculinity: he reads and draws, is quiet and emotional, and shows fear instead of anger.

Road to Ladakh (2008)

Once again I am biased, dear travellers: one of the protagonists of this short film (it lasts less than an hour), is Irrfan Khan, who unfortunately is no longer with us, and whom many people in Europe remember from “Life of Pi” and “The Millionaire” and of whom I will speak later.

The story seems trivial: it is the tale of mistaken identity between a coke-addicted model and a taciturn stranger. They meet on a trip to Ladakh, in the Kashmir region on the border between India and Pakistan. Actually, there is much more behind the story of this film: long before Irrfan became an international star, he showed up in Ladakh (with a broken arm) to take part in this project. He endured sleeping in tents that flooded, he suffered from mountain sickness, but he kept his commitment to the director (a first-time director, by the way). And for his role, he was not paid!

Moreover: with the rapid onset of the monsoons, it was imperative that the shoot be completed in a demanding sixteen-day schedule. A convoy of fifteen vehicles and two trucks carrying generators, camping equipment, a huge crane and a tent, drove over the Rohtang pass and into the Spiti Valley, where it never rains… or so they say. The disaster happened during the descent from the 4,500 metres of the Kunzum Pass. In an area where no one had seen rain for a decade, it started raining during the movie shoot. The work, therefore, had to stop. Tents flooded as temperatures plummeted. A fever struck the production crew. Six days out of sixteen were thus lost, but … the film was then fortunately produced and now only awaits your eyes.

Amal (2007)

Amal (2007)

A poor rickshaw driver from New Delhi is the hero of the title. From its opening frames, ‘Amal’ conveys a vivid sense of everyday existence on the streets of the Indian capital, where the gentle, bearded Amal Kumar drives passengers in the rickshaw he inherited from his late father. When one of his regular customers, the beautiful and headstrong shop owner Seth (Koel Purie), loses her purse to a young street urchin, Priya (Tanisha Chatterjee), Amal chases the thief on foot, only to watch in horror as she is struck by an oncoming vehicle. Amal’s response to this situation reveals his fundamentally generous nature. So does his treatment of another passenger, the bad-tempered G.K. Jayaram (Naseeruddin Shah), whose irascible insults and impatience fail to penetrate Amal’s calm and deferential attitude. What Amal doesn’t realise is that Jayaram, apart from his scruffy outer vestments, is a dying millionaire.

Water (2005)

I conclude this first article dedicated to Indian cinematography with ‘Water’, another movie with focuses on the condition of women. This is an important story for several reasons: set during Gandhi’s rise in 1938 in the holy city of Benares, it focuses on the hardships experienced by Hindu widows, still a problem today in a country with 33 million widows. “Water” is the story of eight-year-old Chuyia.

Her marriage, which she does not even remember, was arranged by her family for financial reasons and does not last long because Chuya is soon widowed. According to ancient Hindu texts, in life, a woman is half her husband’s and if he dies, she is half dead. A widow, therefore, has three choices: she can throw herself on his funeral pyre and die with him; she can marry her brother if one is available, or she can live out the rest of her days in isolation and solitude. If she chooses the latter, the ascetic path, she enters an ashram, shaves her head, wears white as a sign of mourning and tries to atone for the death of her husband. Chuya is taken by her parents to a dilapidated ashram, where she sleeps on a thin mat in a room with older, infirm women whose solitary life has been spent in renunciation. They sing religious hymns every day and beg in the streets. People avoid them like the plague; many Hindus believe that if they come across a widow, they will be polluted and have to go through purification rituals.

The film is important because it depicts the terrible damage that can be done to the human spirit when chauvinistic religious rules and texts are treated as sacrosanct. The inhuman treatment of widows in India by Hindu fundamentalists is similar to the subjugation of women by Christian, Jewish and Muslim fundamentalists elsewhere. It is appalling to see religion being used to deny the dignity and rights of women.

That’s all for this first episode. In a few weeks, I will tell you more stories from the Seventh Art.

In the meantime, let me know if you liked this overview and found this article useful.

Thank you for the trip and nice descriptions Marion

You’re very welcome 😉