Miss Sarajevo

This is a series of short stories about love and trust in others. A utopia in these disintegrating times.

12 years later

12 years later

After 12 years, I went back to Sarajevo in June 2023. The night before departure I cannot sleep well: I am positively nervous. Beyond this last night at home, I feel like a friend I haven’t seen for too long is waiting for me: will I find differences? How will she have changed? How will I have changed towards her? Because everything evolves, the world is touched by a continuous, absurd, and fascinating becoming, but we also change as travellers: we remove certain interests, we replace the eyes with which we look at what surrounds us, we focus on new elements and leave out others that, years before, had seemed unmissable.

My arrival in Sarajevo was delayed because I got stuck one night in Frankfurt. In my working life before this one, I used to pass through that airport a couple of times a month, but the terminology for delays never changes: ‘technical reasons’. But then comes this city that – inexplicably – I love with all my heart: I first see it from the plane window and then start to see it coming towards me as I sit on the bus that takes me from Butmir to the centre in half an hour (ticket 5 Marks – June 2023). By a strange play of mirrors, I feel as if I had never left here: those little houses leaning on the hills surrounding Sarajevo are strangely familiar to me, and I can’t help thinking about what it must have been like then during the siege, and what life is like now in this history that I feel is mine, but which doesn’t even remotely belong to me. I think absurd thoughts as people get on and off the bus: is it possible to think that our souls are actually capable of crossing eras and borders? Why, if this is not plausible, do we feel at home in places that do not belong to us?

Jemal

This time, I stayed in Sarajevo for a week: I didn’t organise any travel outside the capital because I wanted to enjoy it thoroughly. A 10-minute walk from the Sebilji fountain, I booked a small flat. I stop at a small supermarket to get something for breakfast: for once, I am not in a hurry. I am in the moment, there is nothing but the hustle and bustle of people in Baščaršija. From one of the many mosques in the old city centre, the muezzin’s call to prayer begins. How do you explain a city like Sarajevo to someone who has never been there?

At the flat, Jemal welcomed me.

‘You must be hungry and tired after all this road: I’ve left you some baklava in the fridge and some strawberries. See, they grow in my pots outside,’ he told me in highly understandable German. A welcoming ritual that would be repeated for all the days I would spend in Sarajevo: Jemal is over seventy years old, he worked in the Red Cross even during the war, and from his actions and the scars on his face it seems to me that he understood long ago that kindness travels further than atrocities. He would also leave me chocolate and freshly baked bread in the window, and without ever intruding on my routine, every night he would ask me what I saw in his town and what I ate that was good. On the last day before he took me to the airport, we had tea together in his rose-filled garden, like two old friends.

Eliana

Eliana is my piece of Italy in Sarajevo. She is a friend of a friend. She could also have told me no, that she had no time for me when I contacted her because, after all, we are two strangers. She has lived here for many years and raised her two beautiful children here, who speak five languages fluently and are beautiful and intelligent. Her daughter greets me by giving me a drawing that now hangs in my bathroom: she drew blue giraffes and waves. She tells me she likes animals as she hands it to me in their flat overlooking the Miljacka.

I look at this family in which languages, cultures, and traditions intertwine, and I immediately think of Ivo Andrić, the storyteller of multiculturalism in his book “The Bridge on the Drina”: in it, he recounts the centuries-long coexistence of Muslims, Orthodox, and Catholics in Ottoman-ruled Bosnia from 1500 until the First World War.

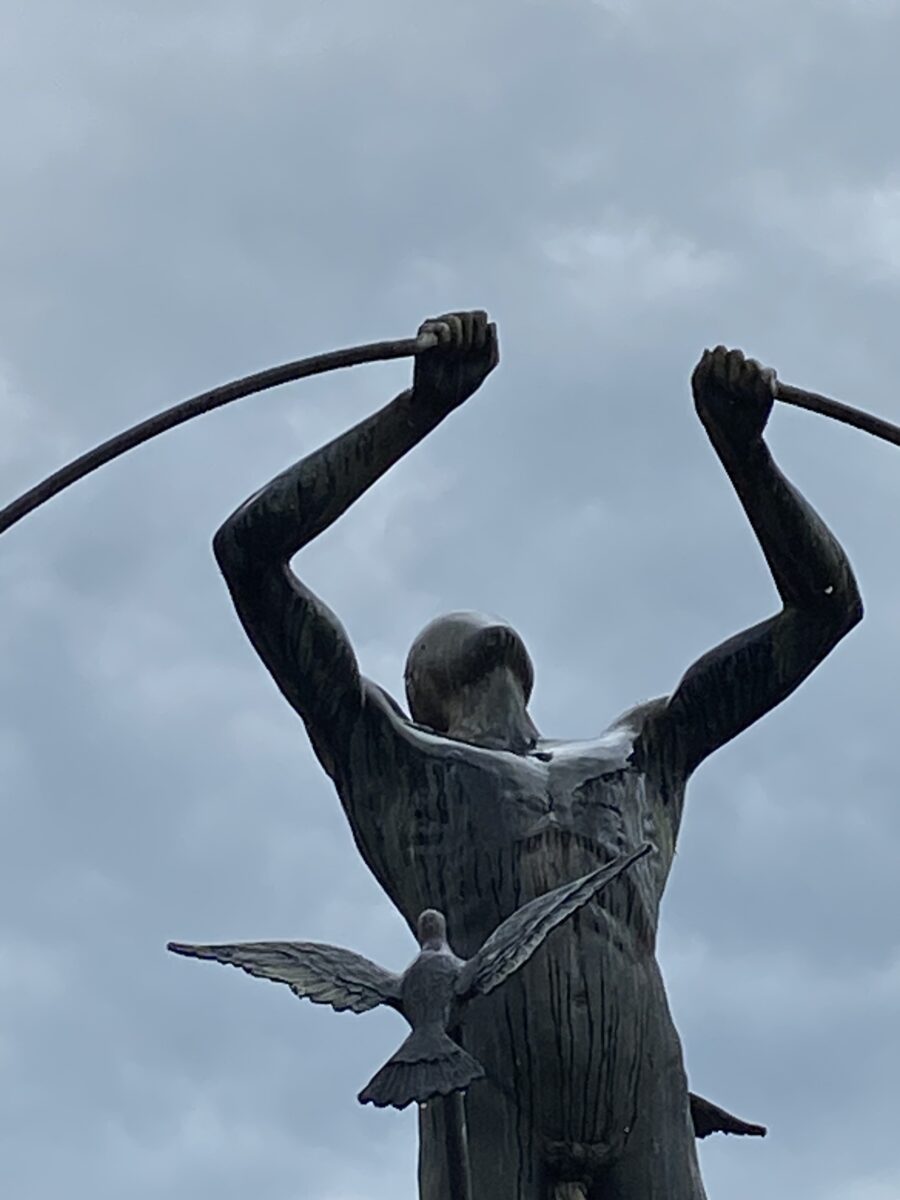

I am also instantly reminded of Francesco Perilli’s sculpture in Trg Oslobodenja (Liberation Square): the phrase underneath that man breaking the circle of wickedness and racism says that “the multicultural man will build the world”.

A shocking and almost utopian sentence in our dissociating times.

The Vrbanja Bridge

The next day, I walk slowly towards the Vrbanja Bridge.

It was here, on 19 May 1993, that Boško and Admira were murdered as they tried to flee the ethnic hatred that had torn Sarajevo apart and turned it into a slaughterhouse. Admira Ismic was a 25-year-old Muslim girl. Boško Brkic was her Serbian Orthodox boyfriend. 25 shots fired by Serb snipers stationed in the mountains surrounding Sarajevo during the siege of the city ended their young lives. Their bodies remain clutched to each other, on the ground, for eight days. There is no gravestone to remind everyone that love is always stronger than hate: I asked around about the reason for this lack, and no one could give me an answer.

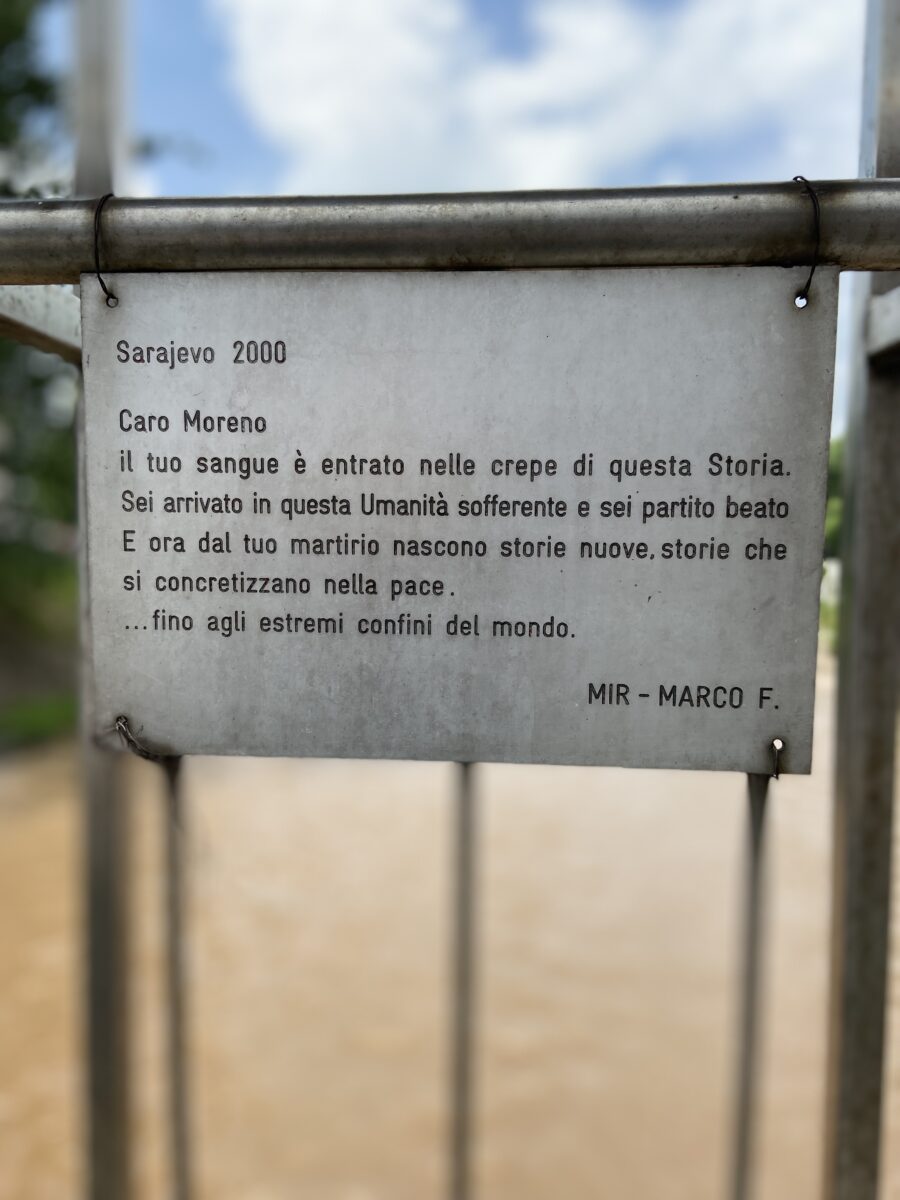

But the Vrbanja bridge is also important for other reasons: the young Italian pacifist Moreno Locatelli lost his life here. On 3 October 1993, with four other pacifists (Luigi Ceccato, Father Angelo Cavagna, Pier Luigi Ontanetti, and Luca Berti), who with him in Sarajevo are carrying out the project “Si vive una sola Pace”, Moreno is crossing the Vrbanja bridge over the Miljacka stream that divides the city, for a symbolic action aimed at the two sides in the conflict: they want to lay a garland at the site of the first civilian victims of that war (Suada Dilberović and Olga Sučić, killed there by a sniper on 5 April ’92), and then offer bread to the Bosnian and Serbian soldiers, who face each other from the opposite sides of the bridge; the conflicting militias have been warned of this small demonstration. Moreno is hit by sniper fire when he and his comrades are retracing their steps following some warning machine gunfire. He died after two surgeries, and his last words were “Is everyone OK?” referring to his comrades on the bridge.

But the Vrbanja bridge is also important for other reasons: the young Italian pacifist Moreno Locatelli lost his life here. On 3 October 1993, with four other pacifists (Luigi Ceccato, Father Angelo Cavagna, Pier Luigi Ontanetti, and Luca Berti), who with him in Sarajevo are carrying out the project “Si vive una sola Pace”, Moreno is crossing the Vrbanja bridge over the Miljacka stream that divides the city, for a symbolic action aimed at the two sides in the conflict: they want to lay a garland at the site of the first civilian victims of that war (Suada Dilberović and Olga Sučić, killed there by a sniper on 5 April ’92), and then offer bread to the Bosnian and Serbian soldiers, who face each other from the opposite sides of the bridge; the conflicting militias have been warned of this small demonstration. Moreno is hit by sniper fire when he and his comrades are retracing their steps following some warning machine gunfire. He died after two surgeries, and his last words were “Is everyone OK?” referring to his comrades on the bridge.

As I stand there, in one of Sarajevo’s many tragic places, Ivanka approaches. She is also in her seventies, like Jemal. She was born in Croatia, but long before the war, after the death of her parents, she left for Africa where for a long time she did an incredible series of jobs: she drove cranes in South Africa and then founded a fast food company. From there, she moved to New Zealand where she obtained citizenship, where her children were born, and where she divorced her husband.

The last time she was in Sarajevo was on her honeymoon at the age of 18. “The only thing that relieves me is that my parents died before the war: that would have been a nightmare because mine was also a mixed family,” she tells me. She is not interested in politics because it only complicates things. We end up spending the whole day together: we go for a coffee and then have dinner together and tell each other a bit about our lives. It is strange how sincere one can be with strangers sometimes.

These things do happen

I spend my days wandering around this city. I take very long breaks to observe the hustle and bustle of people and travellers, and to drink coffee the way they drink it here: in Sarajevo, coffee is served in the ‘džezva’, a plated copper pot with a long neck, along with a glass of water, some sugar cubes and small rose jellies called ‘lokum’. A real ritual, not a lame tourist thing.

I decided to visit the museum of crimes against humanity and the genocide of 1992-1995. It is rich in archival material and offers a multidisciplinary approach to understanding and researching the events in the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the period 1992-1995: Sarajevo was under siege for more than 1400 days, holding the sad record of the longest siege in the modern world. Every day, 329 missiles fell on the city. More than 18,000 people lost their lives during those years, and more than 300,000 were injured. I could go on with more data, but if you ever pass through Sarajevo, go and visit this museum: it is an atrocious and atrophying proof of how little memory we continue to have of wars and violence (I talked about this concept in this article in early summer 2023).

To recover a little from this complex visit, I walk slowly along the Miljacka and stop to look at the Acrobats. These statues were hung above the river during the first months of the siege. They conveyed the message that art could not be stopped, even in such horrible circumstances. The human spirit and freedom represented by artistic expression could not be broken. During the thousands of days of siege, more than 40 works were performed in the theatres of Sarajevo, despite the fact that hundreds of missiles were fired at the city every day. They are a symbol of the resistance of humanity, despite everything, despite the chaos.

I then decided to take part in one of the many free walking tours that are now everywhere in the world: this walk lasts more than three hours and I chose it because it is dedicated to the wounds that the 1992-1995 war left around the city with an in-depth look at how much Sarajevo has changed in recent years (I booked the tour with GuruWalk – ask for Neno as a guide leader if you can, he was great). The tour ended at 5 pm and I calmly walked back to the flat, but at the entrance to Baščaršija, someone touched my shoulder. I turned around and was confronted by two German guys who told me that my backpack was open. In a nutshell, someone had taken my wallet. It is the first time something like this has happened to me in all the trips I have made around the world. I felt bad, but I was not particularly shocked because I realised that inside the wallet I had ‘only’ 10€ and my national identity card. I could have had my passport (so difficult to retrieve these days in Italy!) and more money.

I went straight to the nearest police station to Baščaršija and filed an official declaration. I was greeted by a very kind policewoman who, in very loose English, took my statement and told me that I had to come back the following morning to pick up the form signed by her superior. And so I did the next morning, and then I went to the Italian Embassy in Sarajevo. I had never been to an embassy abroad before, thankfully, so when I rang the bell I did not know how to introduce myself and I just blurted out: “I am an Italian citizen. I would need help”. Like in a film, in a slightly dramatic way almost. They opened the door for me and, while assisting me with the complaint file, the administrative woman smiled at me and said: ‘Unfortunately these things happen everywhere, but you should know that in Sarajevo documents are often found and returned here in our offices. Sarajevans know how important a document is, and how difficult it can be to do it over again’. I looked at her crookedly, from the height of my Western cynicism.

After completing this paperwork, I went back to wandering around the city because something like this could not and should not ruin this trip that I had wanted and waited for so long. I had lunch for a few euros at Buregdžinica Sač (Bravadžiluk mali 2): the smell moved like a cat along Baščaršija, and I decided to follow it. I bought a piece of cheese and spinach burek topped with a generous dollop of light sour cream. It was juicy and warm, but with the pastry still crisp and fresh, made in the traditional way and baked under an iron bell. As I sat outside at one of the tables full of people, I realised once again that travelling also means smelling and tasting what the locals eat.

I then visited (from the outside because the building is closed to the public) the Gospodić house. This dilapidated building holds many secrets and its details feed my imagination. It is not known who built it and for whom. According to legend, the plot of the novel ‘The Lady’ by Ivo Andrić is set in this house. According to other city legends, during the Austro-Hungarian era, a beautiful girl with a freer view of the world lived in this house and was visited late at night by important citizens of Sarajevo. The ‘Lady’s House’, as it is also known, is the only building in the Balkans painted with the luxurious ‘graffito’ technique, which consists of engraving designs on plaster. The motifs are taken from ancient mythology, so the goddess of wisdom Minerva, the Roman warrior Perseus, or Mercury are painted on the wall, while the new era is represented by a young woman in the shadow of modern street lighting. The house was probably built during the Austro-Hungarian period when there was a boom in building and craft activities in Sarajevo, accompanied by the adoption of new building regulations.

I go home late in the evening. Jemal is not here today, he has gone to visit one of his daughters; so I slip into bed and switch off the phone. Little did I know that when I turned it back on the next morning, I would find a message on Instagram from an unknown contact: Alena.

With the simplicity typical of good deeds, Alena tells me that her son has found my wallet. Anticipating my doubts, she told me that she was a local journalist and that, if I wanted, she could send me all her documents to confirm that it was not a scam. I had tears in my eyes as I read her messages. The goodness of ordinary people strangely continues to leave me bewildered. We decided to meet at 5 p.m. at Café Tito and when we saw each other, amidst the now disused tanks, we hugged. At that moment, I realised that it had been ages since I hugged a stranger, but the action happened quite naturally as if we had known each other forever.

Alena spoke perfect English and immediately pulled my intact wallet out of her purse. She introduced me to her son, who was wearing the jersey of a football player I don’t know, and told me: “Just think, when he came home with the wallet, I even scolded him: I thought he had gone to rummage through the rubbish!”. I was astonished because I really didn’t think I would ever get it back. I went on thanking both her and the little one and handed her two packs of coffee that I bought in one of the many coffee shops in town: she didn’t want to accept them at first because “it’s not necessary because the documents are important”. I convinced her eventually, and we sat down with three of her colleagues, all journalists: we drank a couple of beers together until sunset. They asked me what people know and think of Sarajevo in Italy, and I had no logical answer, because in reality I am biased, I have loved their city for so many years. It felt like I had known them for an infinite time transcending the languages we speak and our places of birth. We promised each other that one day we would meet again somewhere in the world. We are still in touch after all these months.

Returning home, I entered Hotel Hecco Deluxe, which is located right next to the Eternal Flame, where the pedestrian Ferhadija Street meets Marsala Tita Street. However, the entrance is inconspicuous and easy to miss: once inside the building, I took the lift up to the eighth floor and then climbed another floor to reach the café. There was the whole of Sarajevo in front of me from up there. Ferhadija Street, some large buildings from the time of Austria-Hungary, and the temple towers of different religions: the Catholic Church, the Orthodox Church, and numerous mosques. It is from here that one can clearly see how multicultural Sarajevo is and why the city is often called ‘the European Jerusalem’.

Always great stories. Glad you got your wallet back V.

Thank you! This journey was a source of love and of belief in humans in these upsetting times.

Is “be my friend” still in existence? I knew them in 1996.

I’m not sure, I’m sorry! Was it a cafè? A restaurant?