Ohrid Lake – North Macedonia

“Time never dies. The circle is never round”

I sat at home imagining a world that was motionless during those long months. The cinema came to my rescue because my head could not even remotely focus on the written page. Among the hundred or so movies I watched during that time, there was one in particular that saved me. “Before the rain” (or “Pred doždot” in the original language), released in 1994 and directed by Milčo Mančevski, saved me because, for the first time in that time span that now seems eternal and simultaneously distant, I thought: “When all of this ends, whatever it takes, I’m going there“.

“Before the Rain” could not leave me passive: it is a circular story, a tale of ethnic, racial, economic, and cultural divisions, in a part of Europe that I love and that few have heard of and even fewer could identify on a map. ‘Before the Rain’ is an album of faces and images of a civil war that makes no noise, which very few have read about in high school history textbooks. However, it is also a film about hope: the main characters seek an escape route by reopening the circle that history and the system seem to have drawn around their lives, forcing them to repeat the same choices, the same identities, over and over again. “Before the Rain” is divided into 3 episodes and for each of them there are different endings: which one will the protagonists choose? Will they remain entangled in the destiny of their own culture, or will they choose to break ties with the past?

In July 2022, I went there. And “there” was North Macedonia. To be precise, “there” was the Lake Ohrid area. The following stories make no claim to guidance or value – as always on this site, I write randomly about encounters I have made on my travels. Make of them what you will.

There is always a strange story about cars

As had already happened in my other Balkan stories, I had booked a modest car, but arriving at Skopje airport (direct flight from Turin with Wizzair.com), they inform me that no, they do not have a modest car. They gave me a car that should be driven by a pimp. However, I take the keys with a big smile, and head out of the modern and clean terminal building: I don’t even bother to argue because I feel like I am wronging the guy from the rental agency. Pick your battles, they say.

And in an instant here I am speeding first along the Friendship Highway, and then on the one dedicated to Mother Teresa. Road user charges in North Macedonia are based on the distance travelled, and the tolls are only ridiculously cheap when compared to those we incur in Italy: about 190 kilometres of road surface that is nothing short of perfect and without roadworks cost me 180 dinars, a little less than €3, to be paid in cash. At some of the barriers, however, there are veiled women begging in the middle of the traffic. No one seems to stop or look at them.

Leaving the motorway, I drive along a side road paved with mosques that gleam amidst the usual half-abandoned structures. I smile with love every time I am in this part of Europe and meet these half-done buildings because those who don’t build the second floor of these houses are basically saying: “Let’s see how it goes, OK? Maybe in a year’s time, we’ll have the money to go ahead”.

I pass through the Mavrovo National Park where the very few specimens of the Balkan lynx that have not yet been exterminated by man are said to live. They call them ‘the big cats with few chances’. No, I don’t even see a shadow of them and surely that is a good sign. They are right to be afraid of us, these huge cats. On the shores of Lake Mavrovo, I take a short break: they say there is a church dedicated to St Nicholas, now almost completely submerged by water following the construction of yet another hydroelectric plant. Of this religious building, which can be visited during dry periods, I only catch a glimpse of the tip of the bell tower.

From there on, although I never cross the border, it is all a succession of giant Albanian, and then Macedonian, and then Albanian, and Macedonian, Albanian, Macedonian flags. A game of who’s got the biggest. An endless circle, like the one that Mančevski’s characters talk about.

Italia Super, follow me

Around 5 o’clock I arrive in the town of Ohrid.

Heaven forbid, though, that I make popular or commercial, or for once, comfortable choices! I have booked a room in a guesthouse in the small hamlet of Dolno Konysko, about 8 kilometres from the centre, from which – hopefully – one should enjoy an unforgettable view of the lake that already looks like a sea. With about 10 minutes to go, however, the GPS decides it has had enough. It shuts down and there is no way to restart it. Phones are not really an option here, because roaming is still applied in North Macedonia and the costs are quite expensive. In the heart of Europe, but not in Europe, paradoxically.

The navigator, I was saying, goes off and I take the only route I shouldn’t have taken: a narrow, downhill cul-de-sac, but above all, a small road crawling with cats. I stand corrected: of tiny little kittens, popping up everywhere, above below, left, and right, they almost seem to rain from the sky. I can’t do anything but get out of the pimp car and start screaming for them to run away and avoid running them over. I then do a textbook reverse, and without burning the clutch, I manage to stop on the road, obviously lost.

A car that is certainly more modest than mine overtakes me at hypersonic speed, only to come to a halt a few metres later. The driver also does a textbook reverse and pulls up next to me. I imagine he asks me if I need anything in Macedonian. I answer first in English – who knows why – and then in Italian. Out of the window comes a little girl, tiny like the kittens, who looks at me fixedly and shouts: ‘We speak Italian too, you know’. The driver, in splendid Balkanized Italian, asks me for the facility’s phone number. He calls Goce, the owner of my guesthouse, and then jumps into the car and says: ‘Follow me, Italia Super! Let’s go to Goce’. And we meet Goce at an intersection about a kilometre further on; they exchange a few words in Macedonian, and a pat on the back. My saviours speed off shouting ‘Ciao Italia Super’, I don’t even have time to offer a thank you, they fly off.

Goce’s guesthouse is really modest but clean. Goce speaks 500 languages, and he speaks them all at once as he shows me where to park and then takes me to my room: I am the only guest in the establishment, he tells me, so I can use whatever I want. I have a nice balcony overlooking the hill, and then a patio from which I can watch the sun go down into Lake Ohrid every evening. On my last night there, Goce will leave me a present on the entrance table: olives, figs, and a feta-like cheese, which I will put together with some tomatoes and eat sitting under that patio. Turin from here seems incredibly distant, indeed, it seems as if it no longer exists, because travellers really do live twice.

The most striking facts

Lake Ohrid, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1979, is the oldest lake in Europe and one of the oldest in the world. In its blue waters that make it resemble an infinite sea, two-thirds of which are in Macedonia and the rest in Albania, live more than two hundred endemic animal and plant species, making it consequently one of the most important natural places on the planet.

Lake Ohrid is, however, much more: its shores are dotted with 365 monasteries, one for every day of the year. Or so, tradition has it. Many of these places of faith have disappeared or are simply closed to the public, but in those that I manage to visit, I will almost always be the only non-Macedonian traveller. Or at least one of the few female visitors in general, even though in this little-known region of our continent everybody met and clashed for centuries: from the Illyrians to the Macedonians, the Greeks, the Albanians, the Kosovars, the Byzantines to the Ottomans and even the Franciscans.

Lake Ohrid is also very clean: several times during my stay I put on my swimming costume and go for a swim, and stop to sunbathe. The bathing facilities that decorate its shores are modern and full of life. The beaches that wind around the lake are for the vast majority free and spacious.

Saints and words

The Monastery of St Naum stands about 20 kilometres from the town of Ohrid and about a couple of kilometres from the border with Albania. The radio jumps between one language and another in this area: in doing so, it brings back phenomenal memories of another trip and a wedding a few years ago, on the other side of the border.

There are no cars in the car park (cost: 40 dinars = 0.60€ – July 2022) when I arrive early in the morning. One section of the monastery complex overlooks the lake, always that crazy blue, where there are beach beds like in a resort; the other overlooks the Drin river, from where small boats take visitors and worshippers up the clean, clear river waters like those of an aquarium. Everything is neat. The only rather exotic element is the presence of signs warning that the peacocks – who roam free everywhere – are, alas, aggressive.

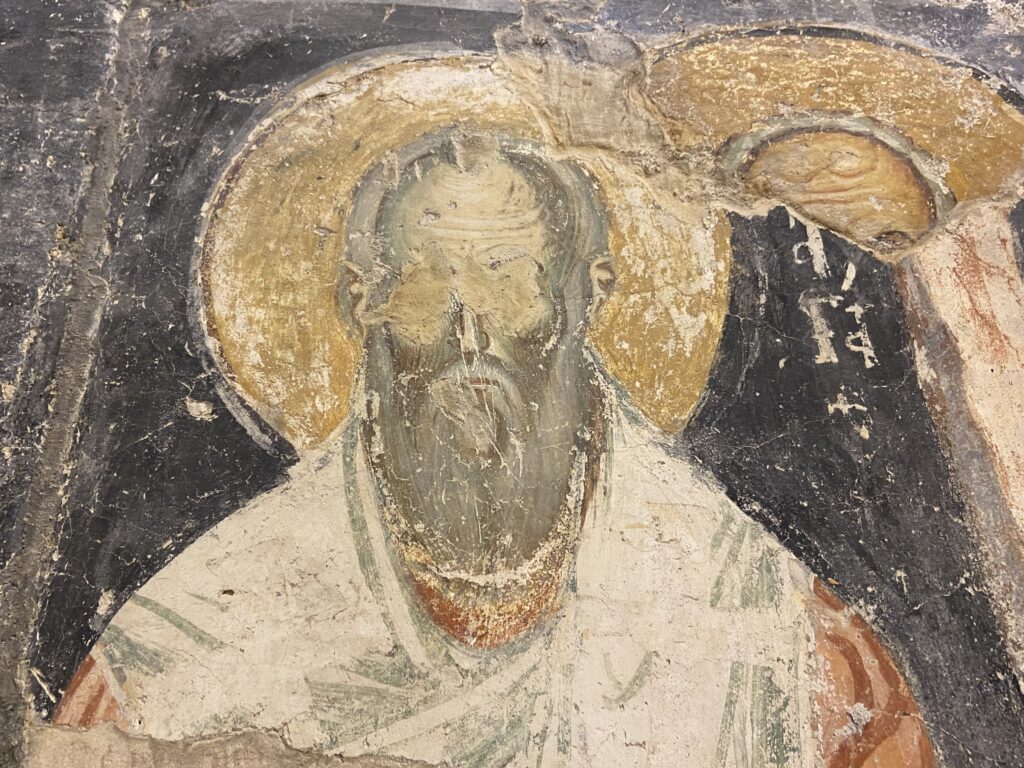

In the main church, there is the tomb of St Naum: legend (because there is always a legend in the Balkans) has it that you can still hear the saint’s heartbeat here. What I can hear is perhaps only my own heart, pounding loudly in my chest as I look at the paintings on these walls dating back to 800-900 AD.

In addition to the tomb of St Naum and a few other newer churches, there is also an extensive Macedonian Defence Department camping site in the monastery complex. Of course, entry is only allowed to those who are/were part of it. The expanse of caravans and campers in the middle of the trees behind the monastery is a surreal sight, to say the least: the weapon, peace, the sacred, and war.

At the Juan Kaneo Monastery (entrance fee – 3€ July 2022), however, I arrive far too early. I leave my pimp car in the centre of Ohrid and then set off following a wooden footbridge over the emerald water of the lake, and then climb up a cliff overlooking the sea. From there, in addition to the majestic view of this expanse of water as old as the world, a series of walks begins. I don’t meet anyone at 8 am, apart from a girl running up here and a couple of residents walking their little dogs. The monastery opens at 10.30 am: the interior is really very small and contrary to my very high expectations, there are not many frescoes.

The Monastery of St Pantaleon and Clement is also located on a hill (Plaošnik). Here things get juicy for language lovers like me: this structure was the site where the first students of the Glagolitic alphabet went to school. Glagolitic is the oldest Slavic alphabet, developed by Saints Cyril and Methodius, tutors of St Clement, in the 9th century AD on the basis of the cursive Greek alphabet, and with some Hebrew and Coptic elements. Beautiful stuff to look at. I wish I could even read it! St Clement, in fact, together with St Naum, would have used the structure to teach this type of alphabet to the Christianised Slavs, thus making it a university. Judging by the architectural style and design of the monastery, researchers believe that St Clement intended his building to be a literary school, which would make it the first and oldest discontinuous university in Europe. After the visit, I stop for a while outside to look at the mosaics that decorate it and think that I would have liked to come to school here.

No eyes, but looking at eternity

If you spend time in the city of Ohrid, please also be sure not to miss the Church of the Holy Mother of God Peribleptos (entrance fee – €3 July 2022), built in 1295. I swear that, even if you cannot take pictures inside, the stories told on its walls will remain in your heart forever. As soon as I enter, I am greeted by the story of the Apocalypse. As often happens, this first illustration served to send a warning to those – the majority – who could not read: if you do not behave well in this life, beware, this will await you at the end of time. Always nice and cheerful, those Christians.

What strikes me most, however, is that most of the figures – in this, but also in other churches in Ohrid – do not have eyes: they were destroyed during the invasions of the Ottomans, who believed that by doing so they were destroying the spirit and strength of those who had supported the building of the church. The structure, however, is important for another reason: it includes intricate frescoes by two Byzantine painter brothers (Mihail Astrapas and Eutychios) who drew here images of the Passion of Christ, the Gospels, the life of the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist. The characters’ faces, however, are not in a series: they all have different expressions, joy, sorrow, crying, and so on. Interpreting these masterpieces with me is the church custodian, who is about 20 years old and studies theology. As I leave, he greets me and tells me that it would be nice if others knew the beauty of this place. So, do me a favour: go to the Church of the Holy Mother of God Peribleptos!

If you liked the story of the erased eyes, then also visit the Cathedral of St Sophia (entrance fee – 3€ July 2022). I get there late in the morning and a concert must have just ended because there are musical instruments everywhere. I wander around for a while observing the picketing that has taken away the view of the characters in the frescoes, and I realise that some faces have even been covered by a thicker layer of paint. As I walk through this church that was completed in the 9th century and also became a mosque for a period of time, I realise that I am not alone. It is not the blind icons watching me, of course. There is another traveller besides me in there. She approaches and the conversation even starts off well: we talk about the scarred icons, the presence of the blue colour of the precious lapis lazuli, and the peace within these walls. Of course, then it all goes to hell: she starts an interminable monologue about the fact that Someone – the very famous Movers and Shakers – has been locking us in for the last two and a half years to change the World Order and create a new human race. She even warms up while talking to me, and raises her voice a little. So I disappear, making excuses that are even more improbable than her ideas.

Parking fees in Ohrid

I’ll try to explain this to you, maybe someone will need this practical travel information. Or maybe not, because I will not be at all clear and you will decide to skip these lines.

You remember the pimp car. Of course, how could you forget it. In any case, I have to park it somewhere when I enter Ohrid! On the first day I decide to leave it near an amusement park, where I find no ticket machine. I go into a phone shop where they explain to me that I have to look for the valet because here they charge from 7.30am until 3am. The cost per hour is about 40 dinars (=about 0.60 €).

On every street or pair of streets – some of them very long, by the way – there is in fact a Man who goes up and down all day, and charges you either when you arrive or when you return. The questions about this system are many:

- How do I find this Man?

- Could it be that if I go looking for him in the meantime, another Man will come along and give me a ticket because I did not show my payment?

- How does he know if I’m telling the truth? That is, I tell it, but … how does he know that I arrived at a certain time, rather than another, if he is responsible for several roads or very long streets?

To all these doubts I found no answer because the lady at the phone shop looked at me as if I had 22 heads when I explained my dilemmas.

For the record, I eventually found the Man after more than 20 minutes of looking for him, and he too spoke exceptional Balkanized Italian.

It smells like Sarajevo

As I walk around Ohrid, the words from Mančevski’s film come to mind: time does not die. When we least expect it, certain things, certain feelings, and memories return. At the table of one of the many restaurants in the town’s pedestrianised centre, a smell flutters cheerfully against my nose: it is the smell of Sarajevo, one of the cities in Europe, in the world, that I love the most. It smells like ćevapi. I order them together with a cucumber and tomato salad and look around: a few steps away there is the Ali Pacha Mosque from which the muezzin’s chant rises, followed by a couple of Orthodox churches, and a Catholic one. At this precise moment, time does a 360-degree turn: I am in a European Jerusalem where faiths and songs at prayer cross paths and probably bump into each other. Like in Sarajevo.

After lunch, I take a walk in the sunshine and arrive in a neat and tidy public garden, in the middle of which a huge Macedonian flag stands out: on the benches, there are many women of different ages chatting with each other. They stand there, together. And another thought crosses my mind: when I travel I always try not to romanticise what I observe, but here it seems to me that there is still some human social fabric, some semblance of non-artificial life. I could be wrong, of course, but I decide to trust my instincts.

Other things not to miss near Lake Ohrid

- Bay of Bones (Plocha Micov Grad) https://www.discoveringmacedonia.com/2018/bay-of-bones-museum-ohrid/. On the way to the Monastery of St Naum, I warmly recommend that you stop and visit this reconstruction of a settlement on stilts inhabited between 1200 and 600 BC. (Ticket price 150 dinars = 2.5€ July 2022).

- Galičica National Park http://galicica.org.mk/en/homepage/. Part of this area is Golem Gradi, the only island in North Macedonia that lies on Lake Prespa. The island is also known as the Island of Snakes, you can easily guess why, but also of a large number of other species, some of them endangered. Ancient Roman and medieval ruins can be found there, and some churches are well-preserved. You can reach the island by boat from Stenje or Konjsko.

Dear Vane, I read this with the sence of being there with you 🙂

Looking forward to the next article!

Thanks so much for the lovely feedback! This part of Europe is so amazing. My writing was just a means to tell you all about it! 🙂