Quito

All departures bring with them specific, individual, and unrepeatable emotions. The one to Ecuador in November 2022 was no different. It was a trip I had to put off several times: first in 2019, when within weeks of starting the adventure I had had to change my destination because the nation had been rocked by several civil uprisings in the country’s major centers; then, of course, the pandemic that had stolen our freedom to go to the end of the world for years.

[Source: https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/145654/three-decades-of-urban-expansion-in-quito]

The excitement, therefore, was especially great when I landed in Quito 35 hours after leaving Malpensa Airport after a series of flights were canceled due to absurd weather situations, technical problems, and adverse gods. I have a very vivid memory of Quito, from the window: it shone like an endless constellation, up there at 2850 meters above sea level, 50 kilometers long (yes, 50) but only 5 (yes, 5) wide. In the grip of a dreadful jet lag, as the plane landed I almost felt as if I could see its 2 million inhabitants returning home after their day’s work, embraced by an incredible array of volcanoes-Pichincha, Cayambe, Antisana, Cotopaxi, and Chimborazo, to list the five most famous and closest to the capital.

I had completely left behind an abnormally warm start to the winter in Turin, but the air that caressed my face once I stepped off the plane was different. It was summer. Indeed, like many parts of Ecuador, Quito has only two seasons: wet and dry. The former runs from October to May and is summer in the capital. The dry season, on the other hand, runs from June to September and is compared to winter. It was pitch dark, too, even though the flight had landed around 8 p.m. Due to its proximity to the equator, much of Ecuador-including Quito-has 12 hours of sunlight year-round. The sun always rises around 6-6:30 am and sets around 6-6:30 pm at night.

At the small guesthouse near the airport (Mariscal Sucre), I only noticed the huge, towering palm trees climbing up the stairs, playing in the warm wind. I was in another world, but even in such a beautiful place, I was so tired: the various stop-overs in Houston, New Orleans, Houston again, and finally San Jose in Costa Rica, had demolished me; so, I went straight to bed on that night and slept like a rock.

Catholic lust

The capital is a city full of architectural beauty that is nothing short of amazing. Thanks to its incredible historic center, in 1978 Quito was the first World Heritage City to be named a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is filled with lush Catholic churches, all the work of the Spanish colonizers who, with the cross in front of their chests and the sword behind their backs, landed on Ecuador’s shores first in 1526 and then, as conquerors, in 1532 when Francisco Pizarro’s expedition, took full control of the nation. As I explore Quito, however, I realize that many of these places of faith remain open when there are masses-I therefore find myself having to retrace my steps several times during my days in the capital at the beginning and end of the trip, but it doesn’t matter because it is worth it.

Among the most sensuous, I remember the Church of the Compañía de Jesús, considered to be the pinnacle of South American Baroque: the particularity that stuck in my mind the most is its geometric, floral, fruit, and garlanded Baroque figures, made of cedar wood, carved and covered with gold leaf. Its altars include images of the founders and illustrious figures of religious communities, such as Santo Domingo de Guzmán, San Agustín, Luis Gonzaga, and Ignacio de Loyola. One of the works that stands out and is seen most often is the painting El Infierno: it is a depiction of what would be the house of Lucifer, who punishes the deadly sins. It is said that back in the early 20th century many mothers took their children to see the painting so that they would know where they would end up if they did not obey and keep the Catholic commandments. The Iglesia is dreamlike and labyrinthine in my recollections (photos are not allowed!) and paradoxically has something Moorish about it, and although I spent quite a bit of time there, I find it impossible to note in my notebook all the details of its architecture that remind me more of a mosque than a Catholic church.

The world – for now – should not end

Another structure to tell about is the Basilica del Voto Nacional, the largest neo-Gothic church in all of South America. It is huge, and as I take a few photos before entering, I realize why the Basilica is often associated with Fear (miedo, in Spanish): it looks like a white, endless skeleton while the faithful are tiny down here praying. The exterior façade is also a surprising experience because it is laden with gargoyles that might seem more familiar than the grotesque fantastical creatures that normally adorn the façades of churches and cathedrals in Europe: in fact, they all represent animals endemic to Ecuador, including iguanas, turtles, armadillos, and condors, and not dragons or monsters.

After paying the entrance fee, I take part in a guided tour in which, a student from the Quito Academy of Fine Arts begins his explanations with the legend that hovers over the Basilica: the world will end if its construction is officially completed. As is often the case in South America, legends merge with political realities and the travails of nations. In 1883, Father Julio Matovelle (a Cuenca-born priest, lawyer, poet, and writer) began gathering support for the construction of a massive basilica in the heart of Quito. The president sided with the project and Congress allocated 12,000 pesos for its construction. Pope Leo XIII approved the construction in 1887, and French architect Émile Tarlier was called in to design the church. Tarlier, inspired by the cathedrals of Notre Dame and Bourges, began his plans in 1890. Finally, on July 10, 1892, the foundation stone was laid. The first mass and the first ringing of the bells took place in 1924. Pope John Paul II then blessed the church in 1985, which was consecrated (but never officially inaugurated!) in 1988 more than a century after its conception.

Elements are still missing in various parts of the basilica, as if to symbolize its continuous becoming: at the main entrance, for example, statues have never been placed to welcome the faithful. Legends are not to be trifled with.

Our Lady with Wings

La Virgen de el Panecillo is magically glimpsed in the Basilica’s main rose window: again, the story goes that this was not a premeditated and planned architectural solution by those who built this marvel. La Virgen stands on a loaf-shaped hill (hence the name) in the center of Quito, visible from most of the city. In the 1950s, local authorities and religious leaders looked at El Panecillo and all agreed that the bare hill was the perfect place to erect a religious statue.

After years of staring at the hill and discussing exactly what to place there, they finally agreed on a concept: the statue would be a much larger replica of the Virgin of Quito, also known as the Virgin of the Apocalypse, the Winged Virgin of Quito, or the Dancing Virgin, a wooden sculpture just over 30 centimeters tall created by Bernardo de Legarda in 1734. This much-loved statue was a jewel of the Quito School of Art and was revered by the city’s faithful. The project was formalized in 1969 and construction of the concrete base began in 1971. Completion of the base alone took three years, largely due to financial setbacks caused by the expensive volcanic stone coating chosen to cover the concrete. For the statue, the committee turned to Spanish sculptor Agustín de la Herrán Matorras. From his studio in Madrid, the sculptor designed and built a replica more than 40 meters tall of the Winged Virgin, using 7,400 pieces of aluminum, with each piece clearly numbered. The statue was then disassembled, shipped to Ecuador, and reassembled on the concrete base. The unveiling took place in 1975, and this time it does not seem to have brought with it any end-of-the-world legends.

But. There is a but, of course. Our Lady does not usually have wings, right? The detail of wings, which had never been seen in any Virgin created before, is due to Legarda’s thought that if she did not put them on, her saints could not reach heaven.

La Calle de La Ronda

Besides the churches and flying Madonnas, one of the most exciting streets in Quito is Calle La Ronda.

The history of this street dates back to the 1400s when it is said to have been an Inca trail. Spanish settlers then renovated the street in the 18th century, and in the early 1900s it became a favorite haunt of artists, poets, and musicians. Although it has been almost a year since I went for a walk along the Calle, I still remember the colorful Spanish-built houses along the street and the wrought-iron balconies adorned with colorful flowers. I also remember meeting two young men assigned by the municipality to complete the census and then leaning inside the gates to see a series of courtyards that looked like something out of a painting.

Along La Ronda, there are also several informative signs explaining the history of certain buildings: among these buildings is El Murcielagario (Bat House), a secret underground bar frequented by musicians in the 1930s. Over time, craft workshops and galleries have settled in the old houses: chocolatiers, milliners, silversmiths, and musical instrument makers ply their trade here. The sounds of live music waft from brightly colored and questionably decorated bars. The aromas of local delicacies, such as quesadilla fresca (a flour or corn tortilla filled with cheese) and the scent of canelazo (a hot drink made with spiced fruit and rum), go to fill the nostrils of travelers lucky enough to arrive here. Children play hopscotch and El Sapo (the toad), which involves throwing coins into the mouth of a brass toad.

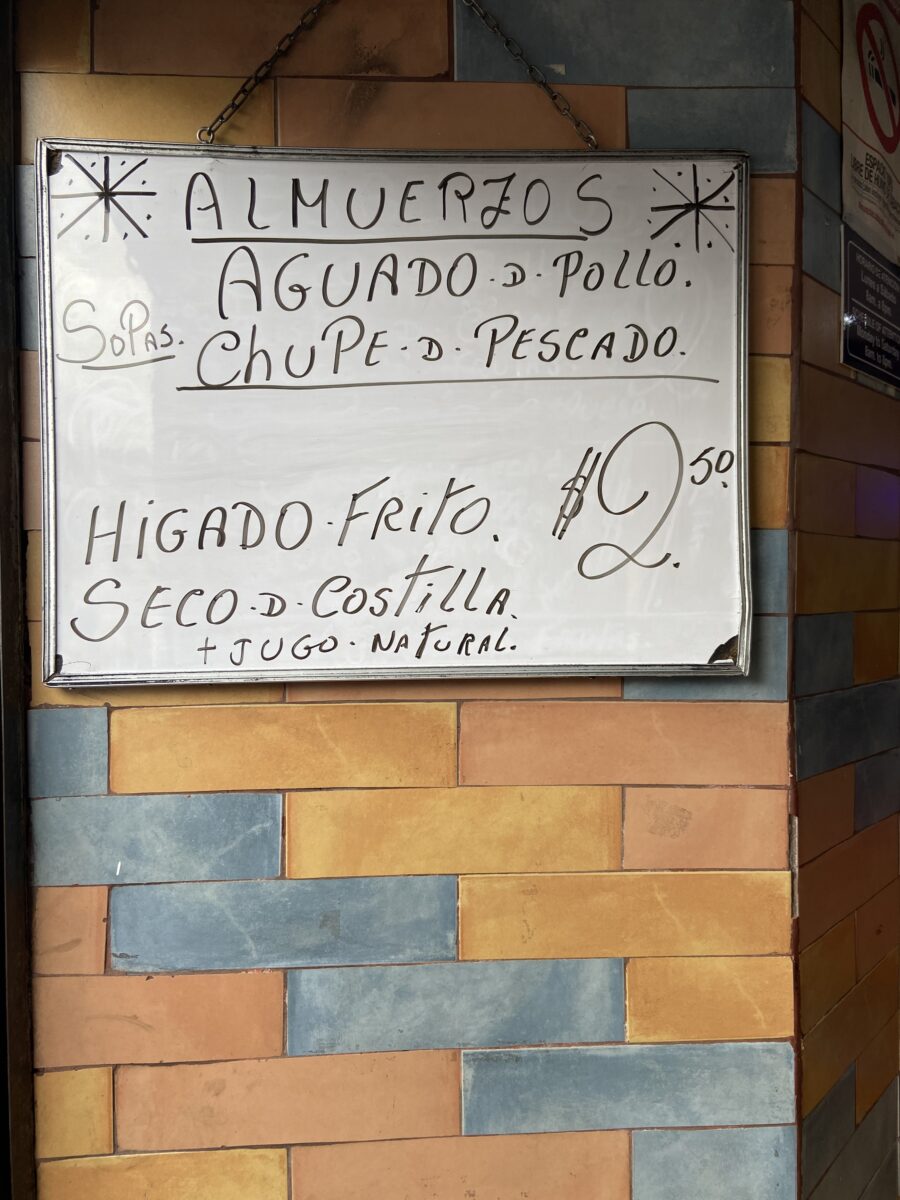

At the end of La Ronda, I stop at a little restaurant that offers amuerzos, the typical lunch combination. For $3-4 (yes, U.S. dollars, Ecuador’s official currency as of November 2022), I can eat a potato, avocado, and cilantro soup, and a main course which is often meat-based: secho de chivo aka lamb, churrasco aka grilled beef with two fried eggs, and more. Once again I will not be hungry!

Sacred and profane, beauty and harshness

In the days I spent in Quito, besides the beauty, I quickly realised how complex everyday life is in mainland Ecuador, especially when compared to those who live instead in the Galapagos Islands. In Plaza de la Independencia, for example, I stop to photograph a series of shoe shiners, some official and some impromptu, but all men. If I close my eyes, I still seem to hear the sound of the brushes their tired hands ran over the shoes of those who could afford a habit that seems so out of time in my Europe, so wrong in ethical terms. They read the newspapers, these local squires, while the curved backs of the shoe-shiners move almost in concert, up and down, right and left, nonstop.

As I grab a coffee at a café in the square, one of the shoe-shiners approaches the table next to mine where two huge German tourists had left leftovers just moments before. Without making eye contact with me, the boy reaches out and eats what little is left of their fat meal. In the evening on my way back to the hotel, a child sucks glue from a bag. He sits on a colorful staircase, those lifeless eyes: it has been since Bucharest and Moscow that I have not encountered social unrest and social despair like this. In a neighborhood parallel to the one where the Basilica del Voto Nacional stands, I am stopped by police who advise me to put my backpack in front as I walk up a street full of prostitutes toward the Infinite Church of the End of the World.

Near the arch of the Porta de la Reina, right in the center, I meet a woman with a couple of goats.

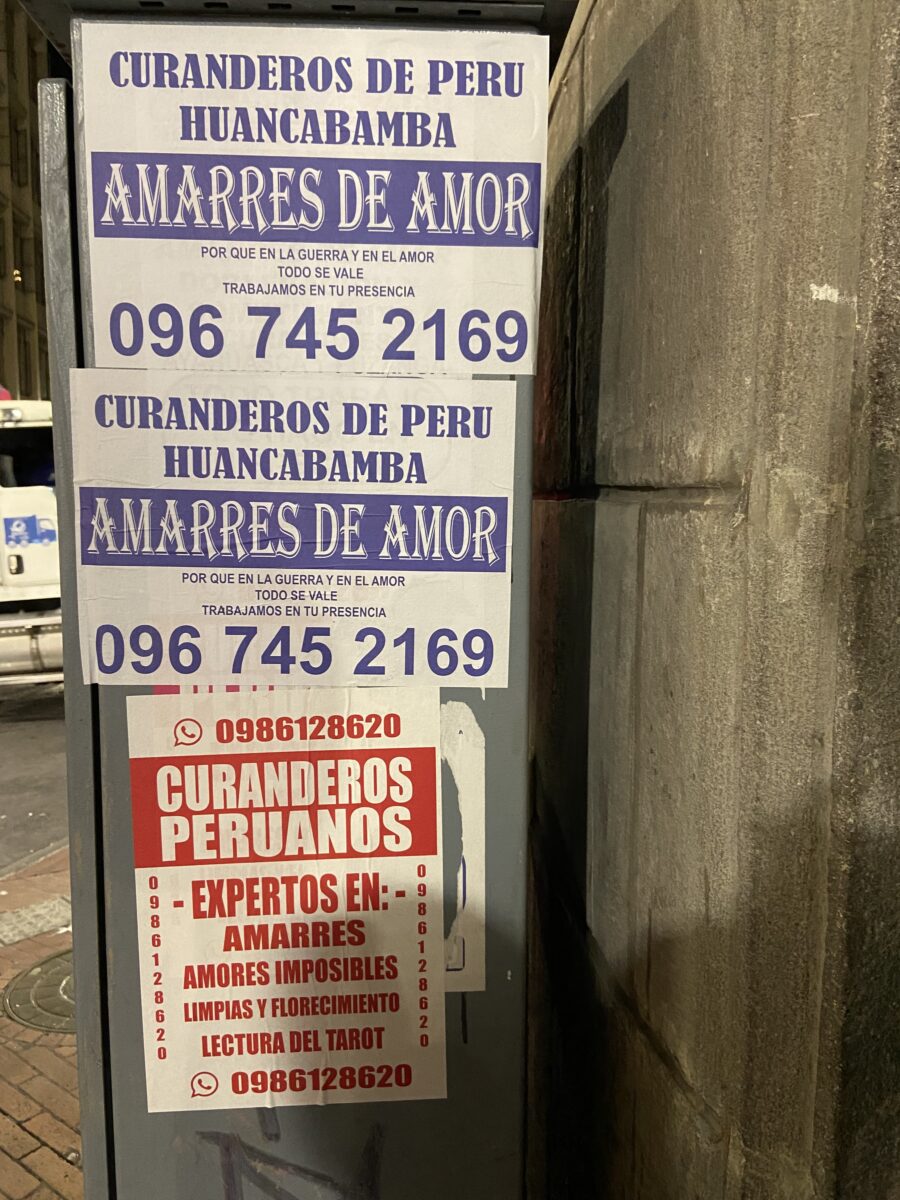

But Quito is much more than just the violence of poverty. Ubiquitous, I smell the scent of Palo Santo, which creates a kind of continuum between the Sacred and the Profane, typical of this part of the world that I love with all my being. The coexistence of science and the occult also manifests itself in the Main Theater Square (closed) where medical and dental centers alternate with stores and esoteric centers that cure any ailment of the mind and body. Then in Ecuador, as in other South American nations, there is also a cohabitation of Catholic faith and shamanism: in front of the entrance to the Church of St. Francis, a woman of indefinite age sells voodoo dolls against Evil that can only be purchased by women. They are white, black, and red, and have a simple structure with two eyes and the rest of the shapeless body, like that of a ghost.

And again: advertisements of curanderos paper the walls and intersections of the city, por que en le guerra y en el amor todo se vale, says one of these advertisements. They treat enfermedad, or the disease that represents an imbalance for which the symptom is not simply treated, but the entirety of the natural, social, and physical context in which the discomfort arises is taken into account: impossible loves, espanto e susto (panic, shock, terror), empacho (intestinal blockage); mal de ojo (devil’s eye, which occurs when a person observes with excessive admiration or jealousy a weaker subject, such as e.g, a child), and mollera caida (the sinking of the fontanelle in children), and much more.

But there is something else

But already from my first days in Quito, I realise that there is more, that there is already something that will make me love Ecuador.

First, there are the Ecuadorians. Unwaveringly positive, they don’t seem to need much persuasion to get excited and welcome you. There it is: welcoming has been, even since Bolivia, one of the main reasons I feel very close to this part of the world. I am sure I am not the only one who secretly loves being called princesa or mi vida when I do something as simple as buying groceries from a rather nice person. And then there are the noises of Quito: three dogs on the balcony howling; two fruit and vegetable vendors shouting out the prices of avocados, eggs, and mangoes with a tone and growl that I’m still not sure were human; the street vendors singing and the megaphones that are used to make their point to the world. Then there is the music. South America’s love of loud, high-pitched music, probably quite annoying if you heard it in my very polite Turin, played everywhere: on local cabs and buses, on stalls, in the hands of young men holding their cell phones.

For all this, and much more of which I will (hopefully) write about soon, I don’t think Ecuador will leave my mind and heart for a long time.