Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer

After all, at least in part, I was a plant

It feels like early summer: the sand I am lying on is warm, I can feel it soft on my back as I look at the completely cloudless sky. In front of me, the Mediterranean doesn’t care: it keeps lapping, splash, splash, splash. It comes and goes, this great sea. It never stops and at the same time, it is never the same. Every time I arrive in front of it, I always think of those who try to cross it and die in the middle of those waves.

Today, however, it swallows up my thoughts, this immense expanse of water: I don’t know if it is possible not to really think about anything, about the past, about the future, but today in front of the Mediterranean I am only observing the present. I am a free woman lying on a beach a few hours’ drive from the city I call home, no one disturbs me, no one bothers me. I am free to stay here on this fine sand even until the stars appear if I feel like it. The concept of Nation no longer exists: I am a lucky woman because borders only exist for me on maps and have nothing to do with my passport, my nationality, my faith.

Lying on the sand, I listen to songs from 17 years ago, when I was still a student at university. Flashes pass through my mind, moments which are totally disconnected from the music, but in them, I have the clear, clean feeling that the pandemic is ending, that despite the pain, I have made it, that most of those I love are doing well. They are fractions of light, little comets.

At the same time, however, the usual exhausting duality that has characterised this part of my life presents itself: it seems impossible to me that I have spent the last two years immobile in the same place. I reflect on what the various lockdowns have meant and realise that, at least in part, I have been a plant: not being able to move around much (as any good animal does in case of danger or need), I have learnt to know every inch of my home and have understood what worked or could be improved in my flat. Not being able to go out for long periods of time, I relied on a modest but solid network of a community (I wrote about it here) that developed extensively thanks to technology and so paradoxically I communicated more, more often, more widely. My family, my close friends, my neighbours have been my roots.

In the long run, however, these survival techniques, being a fragile, naked animal (for the joy and approval of the creationists who read me), could not last much longer: animals do not really solve problems like plants. Animals don’t really solve problems in the same way plants do. In most cases, animals actually avoid problems by running away, by moving somewhere.

So, here I am: dodging the bullet. On a beach. In front of the Mediterranean.

Saint Sara

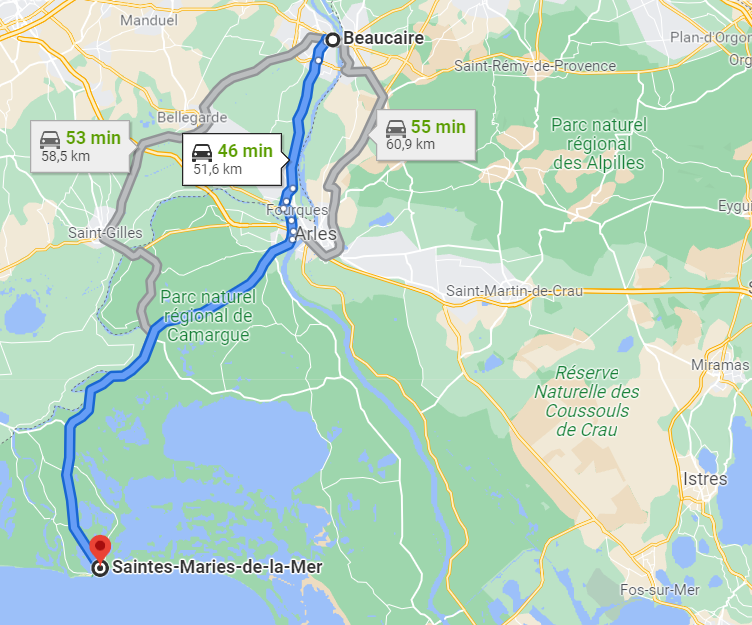

I went back to Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer several times during my French weeks. From Beaucaire, it took me just under an hour by car, and this little village, capital of the Camargue, was a kind of magnet for me.

I don’t know if it has happened to you in your life as travellers, but there are places that keep calling us for reasons that never really become apparent in the course of our existence. Is it a chance? Is it a question of cosmic energy? I don’t have an answer to these enormous existential questions, but I do know that particular cities (such as Sarajevo or Rome) or regions of the world (such as India or the Langhe) keep popping up over the course of my life.

Be that as it may, I’ve been back and forth to this little village, driving along almost deserted roads (given the season), often driving at random without a navigator, stopping here and there to watch the wild horses roam free through the Camargue Regional Park that stretches right just South of Beaucaire.

And at this point, you’ll say: “Come on! What is there to know about this little village?”.

First of all, you should know that, according to an ancient legend, three Marys landed here. Yes, three: Mary Magdalene, Mary Salome, and Mary Jacobé arrived in this part of Europe from Palestine. Besides them, on that boat, there is also Sara The Dark, the servant of Maria Salome and Maria Jacobé, who were present at the cross of Jesus after his resurrection.

Sara is the patron saint of the Romanès peoples of the world, and her complexion is represented in the statue you will find in the crypt of the central church in Saintes-Maries. Often this saint, considered a minor figure by the Christian church, is linked to the Indian cult of the Goddess Kali and follows the theory that many Romanés communities came from India to France in the 9th century. We travel the world to realise that, in the end, no place is really far away, and we are all part of the same ancestral place. Some even confuse it with the Black Virgins that are kept in many places around the planet.

The air in the crypt of the church where I met Santa Sara is very warm: hundreds of candles are lit in front of the statue of this ebony-skinned saint, adorned with necklaces and a colourful cloak that reminds me of a queen and paradoxically brings to mind el tio, whom I had met years ago in Bolivia, in one of the terrifying mines of Potosí (I wrote about it here).

The feast of St Sara takes place every year around 24 May. The celebrations include a procession through the streets and beaches and thousands of Roma devotees go to the church where her remains are kept. On the first day of the feast, Sara is taken from the crypt and carried to the Mediterranean where she is immersed, at which point women splash water on the statue and their children for good luck. An enormous purifying baptism. I imagine the party from then on: the singing, the dancing, the cowboys’ race to the arena, the fortune-tellers reading the palm, the religious ecstasy, maybe even some liberating tears, while life flows lightly in the many small restaurants where you can taste the delicacies of the region.

I also think about what a festival and a place like this mean in a Europe where all too often the Right is back in the limelight: on this side of the Alps, the Front National, on the other, a useless Lega, interspersed at regular intervals with the usual rhetoric describing all Romansh people as thugs and thieves. What are the practical consequences of this dialectic? Is it easy to find work and housing if the population believes these comments with its eyes closed? Is it necessary to hide one’s identity?

A cockerel

The last time I arrive in Saintes-Maries, I buy a sandwich on the fly from one of the many little bars in the village’s alleyways and go and eat it on the beach, because even at the end of October the weather is still incredibly welcoming. This time I’m better equipped: I lay a blanket on the sand and enjoy the polite silence of the few French people who are there enjoying their Sunday. There’s a dog that walks around me and barks as if to say, “Give me a piece of sandwich, bitch”, stretches its paws towards me, then runs away, then comes back, then runs away, then comes back, it looks like a spring, not a dog. Then, all of a sudden, it freezes, looks behind me and runs away.

It runs away because a small procession is coming. And no, it is not the faithful of St Sara. Leading the queue is a smug little boy with a barely-there beard, a plaid waistcoat under which you can see a belly that is anything but spiritual, and a cane on his shoulders. Behind him, a line of very young women, long skirts, hair in the wind, blouses a little too light despite the mild temperatures. Near the waves, the Cockerel stops, places his stick in the water and raises his hands to the sky. A less-than-cool Gandalf, in short.

Then, one by one, the girls approach him, and he begins to manipulate the air around each one of them: it looks like one of those scenes you see around the world, fervent preachers cleansing the auras. I’ve never understood exactly what they do.

At the end of each treatment, the girls walk away from the Cockerel: one sits in tranche in front of the sea, some start laughing, some dance to the sea, some sit directly in the water, and one even strips off and jumps into the Mediterranean in her underwear. At that point, I realise that there are small children running around the procession. There are no men.

Around 2 o’clock, they sat down in a circle and the only one left standing was the Cockerel: he, in his tight waistcoat, stood up and dominated the group of women who looked at him rapt.

Was it a commune? A cult? I don’t know and I couldn’t tell because they didn’t want me to get too close.